[NOTE: Post has been updated to include a section on scale size]

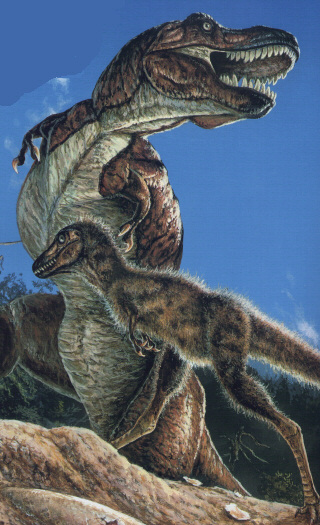

This has certainly been an interesting year. Two papers dropped in the past three months that have put the brakes on a recent trend in paleo-art. That trend? Why the feather-coated T. rex of course.

First, in March, we saw the release of a paper detailing a new species of Daspletosaurus and its relationship to D. torosus.

Carr, T.D., Varricchio, D.J., Sedlmayr, J.C., Roberts, E.M., Moore, J.R. 2017. New Tyrannosaur with Evidence for Anagenesis and Crocodile-Like Facial Sensory System. Scientific Reports. 7(44942):1–11.

In this paper, Carr et al. argue for the designation of a new Daspletosaurus species, D. horneri. The authors argue, based on skull shape and chronostratigraphic position, that D. horneri was the direct ancestor to D. torosus. I thought that the authors put forth a compelling argument for this anagenic event and backed up their position well. Interestingly, this part of the paper should have been the most controversial. As anyone who has read anything from Horner and Scanella over the past eight years can attest, arguing for a direct ancestor-descendant relationship for dinosaurs is difficult to do and even harder to win over others in the field. So it is somewhat surprising to see a case for anagenesis in Daspletosaurus taken so well by the palontological community. All the more so given that it involves a tyrannosaur, the poster children for “cool guy” dinosaurs.

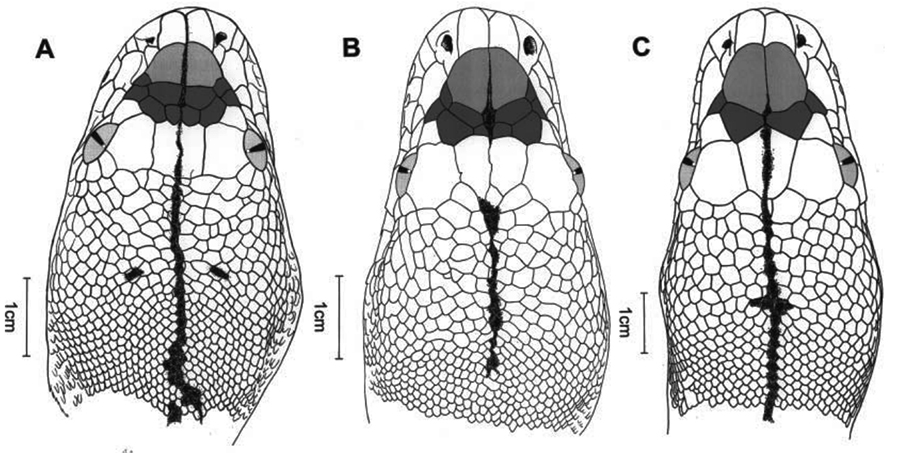

Instead, the most controversial part of the paper wound up being their soft-tissue reconstruction of the face for D. horneri. The author responsible for the soft-tissue reconstruction was Jayc Sedlmayr of Louisiana State University. Sedlmayr did his doctorate on osteological correlates for vasculature in extant archosaurs (birds & crocs). He is the seminal alumnus of the WitmerLab and thus is well within his wheelhouse for this type of soft-tissue reconstruction. Sedlmayr borrowed heavily from the work of another WitmerLab alumnus, Tobin Hieronymus, whose PhD work involved osteological correlates for integument on the skulls of animals. Although the skin is often well away from the underlying bones on most of the body, there are exceptions when it comes to the skull. There, areas that are not heavily muscled, tend to show intimate connections between the skin and the underlying bone. Hieronymus used these connections to determine how different integumentary appendages (scales, hair, feathers) affect the underlying bone (Hieronymus & Witmer 2007; Hieronymus et al. 2009). The authors found that the surface texture along the skull of D. horneri was “hummocky”. That is, it was covered in lots of closely packed ridges. According to Hieronymus & Witmer (2007), this texture correlates to scales as the overlying integumentary appendage. Thus, according to the authors, D. horneri had a scaly face (this is grossly oversimplified as the authors were able to piece together a variety of different integument variants along the skull, but you get the idea).

Scaly tyrannosaur cannonball one had been shot.

Then two weeks ago, we saw the release of another paper on tyrannosaur integument. However, unlike the previous paper, this one was specifically dedicated to integumentary types in tyrannosaurids.

Bell, P.R., Campione, N.E., Persons, W.S., Currie, P.J., Larson, P.L., Tanke, D.H., Bakker, R.T. 2017. Tyrannosauroid Integument Reveals Conflicting Patterns of Gigantism and Feather Evolution. Biology Letters. 13:20170092

In this paper, the authors set out to survey all known instances of “skin” impressions for tyrannosaurids. Their list of taxa included Albertosaurus, Tarbosaurus, Daspletosaurus, and Gorgosaurus. Their results pretty definitively indicated that scales were the predominant integumentary appendage on tyrannosaurids. The authors then went on to speculate why that would be if earlier tyrannosauroids had filamentous integument. They performed an ancestral character state reconstruction based on Parsimony and Bayesian-based trees from Brussatte and Carr 2016. Their results found that filaments came out strongly as the ancestral character for tyrannosauroids, but by no later than Tyrannosauridae proper, a reversion to scales had taken effect. The authors attributed this to body size evolution. Namely, larger tyrannosauroids reverted to scales over protofeathers.

Cannonball number 2 had just been shot.

The new orthodoxy

The response to these two papers have been interesting in light of a very noticeable trend in paleoart over the past thirteen years; the feathered Tyrannosaurus.

In truth, feather-covered Tyrannosaurus depictions have been around for even longer than that. Most notably, National Geographic featured a down-coated baby Tyrannosaurus rex on the cover of their ill-fated 1999 issue (featuring the infamous Archaeoraptor fiasco). However, this depiction of T. rex,or tyrannosaurs in general was few and far between back then. It really wasn’t until the discovery of Dilong paradoxus in 2004, and its phylogenetic placement as basal to tyrannosaurids, that the pendulum start to shift radically towards the enfluffenned T. rex. D. paradoxus was a small theropod, though, so it could still be argued that large tyrannosaurids would have had a sparse feathering, if any at all. This argument stemmed mostly from comparisons to elephants, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus.

However, even this argument fell by the wayside when in 2014, Xing Xu and colleagues announced the discovery of a giant filamented theropod that nested close, but still basal to, Tyrannosauridae. The animal in question was, of course, Yutyrannus huali, an animal that I have written about at great length before. At 1400 kg, Y. huali was not a small animal, and yet it was adorned from head to toe with long, shaggy filaments (likely stage 1 protofeathers). If an Allosaurus sized theropod could still sport plumage, then the argument for other tyrannosaurids being fluffy suddenly appeared plausible.

And so the rampant enfluffenning began.

A cursory Google image search for T. rex, using time limiters for 2004–2008, 2008–2011, and 2012–2017, shows an exponential increase in the amount of enfluffenned T. rex over time. D. paradoxus planted the seed, but Y. hauli set off the bomb.

Now, admittedly, the image above is limited to Deviant Art images only. This was done both to keep the hits relevant (there’s lots of crap out there that has Tyrannosaurus associated with it), but also because of the vibrant paleo-art community on that site. Many dinosaurphiles frequent the website and many aspiring paleo-artists use DA as a portfolio for their work.

Given the fervor with which this trend has caught on in paleo-art, one could imagine that the latest two papers did not go over very well. Both papers have been greeted with intense skepticism. As a scientist, I can respect healthy skepticism about a new study (more studies should be treated this way), but I also expect the skeptics to be skeptical for the right reasons (i.e., the science). In the case of both Carr et al. 2017 and Bell et al. 2017, I have not really seen this play out.

I’m getting ahead of myself here. So let’s take a look at each new paper on its own.

Tyrannosaurid heads: scaly or just cracked?

The largest complaint leveled at the Carr et al. paper was their use of osteological correlates for scales. The reason was that the authors compared the hummocky texture on tyrannosaurid skulls with that of crocodylians. This was done, in large part, because crocs are the closest scaly relatives of dinosaurs. So from an extant phylogenetic bracket perspective, it makes sense.

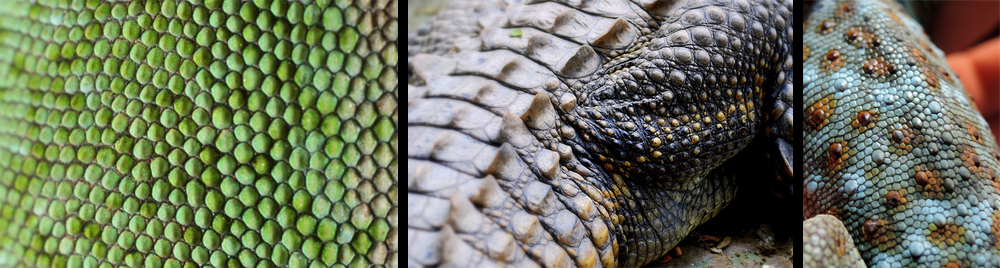

The problem, however, is that crocs don’t have scales on their heads.

Some of you may be crying foul on this, but it’s true. Despite a superficially scaly appearance, crocodylians have recently been found to not have scales on their faces. Work by Michel Milinkovitch and others (2013) discovered that the “scales” seen in crocodylian heads, do not correspond to true, epidermal scales. True scales show serial homology. That is, each scale is a nearly identical unit to its neighbours. There are still variations, but the variations occur across multiple scales, rather than each individual scale. Scales are also consistent between members of the same species (for the most part). This consistency is extremely important for herpetologists, as many lizard and snakes are described by their facial scales. Crocodylians, on the other hand, do not show this consistency. Each crocodylian individual has a unique “scale” pattern on its face, and the pattern is randomly distributed so that no two “scales” look alike (well, barring coincidence). When the authors delved into the development of Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus), they found that the head gets covered in a single keratinous sheath that later cracks due to shrinkage, forming the random, scale-like patterns we see in modern crocodylians (Milinkovitch et al. 2013). The authors argued that this was likely due to the presence of dome pressure receptors (DPRs) along the face of modern crocodylians. These integumentary sense organs form before the corresponding integument and appear to have corrupted the scale-development process, resulting in the strange, pseudoscales seen on extant croc faces.

The implications of Milinkovitch et al.’s work is pretty damning, as it essentially means that neither extant members of Archosauria have scales on their heads. Does that mean that Daspletosaurus horneri and by extension, all other tyrannosaurids were also covered in a cracked, keratinous sheath?

Eh, probably not.

The reason why not comes from the next branch down from Archosauria, Lepidosauria. From Hieronymus et al. 2009 (emphasis mine):

A second form of osteological correlate for scales can be seen in many iguanian lizards, and consists of a regularly arranged, shallow, hummocky rugosity on the bone surface… These features are not related to intradermal ossification and are instead derived entirely from apophyseal bone growth beneath individual scales…

…both of these morphologies [the other one being osteoderms] are considered robust osteological correlates for epidermal scales in extinct taxa.

Reading through their paper, it was apparent that Hieronymus et al. found the hummocky texture on the skull bones of iguanian lizards, not crocodylians (though these were also studied). Thus, the osteological correlate for scales on top of bones comes from data in lizards, and not crocs. Lizard head scales are true scales, so the hummocky texture morphology still holds true. That the hummocky texture was said to be associated with croc epidermis can be blamed on a misread of Hieronymus et al. 2009.

All that said, it is worth bringing up the fact that Carr et al. also argued for the presence of DPRs in tyrannosaurids based on similar neurovascular foramina density to extant crocodylians. This is not the first time that a theropod has been hypothesized to have had a “sensitive” face. Ibrahim et al. (2014) argued for similar facial sensitivity in Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, as have Barker et al. 2017, in their recent paper on Neovenator salerii. If true, these data would suggest that highly sensitive snouts were a common theme in theropod evolution, and that a cornified, but not scaly, face may have followed suit.

The problem is that this is almost certainly not the case.

The DPRs in crocodylians work by sensing pressure changes in the surrounding water. DPRs are the tetrapod equivalent to the lateral line system in fish. Both the lateral line system and DPRs work well underwater because water is an incompressible substance. Thus, pressure waves travel through water as if it were a solid. This is why the speed of sound is over four times faster in water vs. air. Air is comprised of compressible gases that make it harder for pressure waves to propagate very far. The inefficiency of sound travel in air is likely why tetrapods dumped the lateral line system in favour of ears. This means that DPRs are essentially useless out of the water. Any pressure changes that they could detect (barring explosions) would be at distances that are practically on top of the animal’s mouth. Hardly that helpful.

Top image adapted from Witmer & Ridgely 2009. Bottom image adapted from George & Holliday 2013.

Another strike against the super-sensitive snouts of theropods, comes from their brain endocasts. Crocodylian brains show a honking big foramen for the trigeminal nerve (George & Holliday 2013). Trigeminal is the main sensory nerve to the face of tetrapods. A larger trigeminal foramen indicates a larger trigeminal nerve, which means more available neurons to carry sensory information back to the brain. Compared to crocs, the trigeminal foramen in theropods is small. It’s still big (it’s the largest cranial nerve for most tetrapods), but it’s not that big compared to an animal of similar size (e.g., see Witmer & Ridgely 2009). An average-sized trigeminal foramen strongly argues against the super-sensitive snout hypothesis.

So if theropods didn’t have DPRs on their snouts then why do they seem to be so heavily innervated?

The answer lies in the suffix of the term: neurovascular (i.e., nerves and blood vessels). The foramina described by Ibrahim et al. 2014, Carr et al. 2017, and Barker et al. 2017, are known for carrying nerves and associated blood vessels. All the theropods that have been hypothesized to have had “super-sensitive” snouts, were multi-tonne creatures. Big animals have more cells than smaller animals, and those cells need nutrients. What we are likely seeing is the inevitable increase in vascular irrigation to the heads of large theropods. More blood vessels require either larger foramina to travel in, or more foramina to accommodate the extensive branching patterns of the arteries to their associated capillary beds. For big theropods, we see a mix of both. A good way to test this hypothesis would be to take similarly sized theropods and crocodylians and compare their respective foramina densities. I suspect that the crocs will beat out the theropods by a country mile.

Returning to the crux of this post, the complaints that I read online focused heavily on the comparison to crocodylians, despite the fact that the authors used osteological correlates for lizards. I’ve also seen comparisons to other gnarly-textured animals such as hippos, but these types of superficial comparisons are not equvalent. Carr et al. looked a minute details on the skull of D. horneri, and they painstakingly detailed not only the textures seen on the skull bones, but also what layers of textures were present, and the associated profiles those textures corresponded to. This is a far cry from simply looking at a roughened hippo skull and saying it is equivalent to a crocodile.

New tyrannosaur scale paper for old tyrannosaur scale imprints

Turning now to our second paper, the headlines that came out from this study were certainly entertaining. They ranged from groundbreaking find to full-on snark. I found the response from the paleophile community very interesting. In many ways it mirrorred the reactions seen two years ago when Paul Barrett and colleagues released their work testing the homology and ancestral integumentary appendage type of dinosaurs (Barrett et al. 2015). In the case of Barrett et al., the reaction started off quiet followed a few weeks later by blog posts and Facebook rants that took the paper to task over allegedly bad interpretations of the data. The Barrett et al. paper is worth reviewing, and is something I intend to do at a later date. For now, though it remains the only attempt to asssess homology in the filaments found in some dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

The case for Bell et al. 2017 was somewhat similar, except that the refractory period between quiescence and attack was much shorter. Some responses seem more a reaction to how the new articles were written, whereas as others were more even-toned in their critique of the paper.

In general, the complaints against the paper from Bell et al. can be summed up in one of three categories.

- The paper details “skin” impressions that have been known about for decades

- These impressions look no different than a rhinoceros ass / plucked chicken / dirt

- The authors are making blanket statements based off coin-sized samples of “skin”

Let’s tackle each complaint separately.

(1) The paper details “skin” impressions that have been known for decades

This complaint is a mix of fact and fiction. While it is true that Bell et al. looked at integument samples that had been previously collected, many of these samples had only been known by those in the paleo field (i.e., there was never a published account). The exceptions to this were the Wyrex “skin” impressions which were published in a book chapter by Neil Larson, the Tarbosaurus impressions (Currie et al. 2003), and the Daspletosaurus impressions (Currie & Koppelhus 2015). So, yes, in some ways this is old news.

Here’s the kicker, though, most of these published impressions were mentions, not descriptions.

Let’s just look at these grand descriptions real quick.

The Wyrex specimen, which has been known about since 2004, was in privately owned hands for much of that time. It has only recently come to be housed at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, where it received an official accession number: HMNS 2006.1743.01. So despite knowing about this specimen for over ten years, it has only been available for scientific study in the last three years. The only published description of the material came from a book chapter in the 2008 book, Tyrannosaurus rex, the Tyrant King. Book chapters rarely get peer reviewed and are considered “grey literature” for scienfic publications.

So what did this little bit of grey literature say about the skin impressions?

During preparation, several patches of skin (Fig. 1.26B) were found with the skeleton. Most of the skin patches (more than a dozen) were found on the bottom side of the articulated tail. The discovery of skin with Wyrex is a first for T. rex. Plans are currently underway for futher excavation at the site in hope of finding more of the skeleton. — Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King, p: 47.

That’s it. A quick little blurb followed by the now infamous scale photo, is all we had for Wyrex. In contrast, Bell et al. spent an extensive amount of time detailing the various impressions found associated with Wyrex, and where they are located on the body. In other words, they actually described the impressions.

Okay, so what about the other “old news” specimens?

Here’s what Currie et al. (2003) had to say about other tyrannosaurid integument impressions:

Skin impressions (MPD 107/6A, Fig. 5D) were recovered from a Tarbosaurus skeleton destroyed by poachers at

Bugiin Tsav (N43° 52.164′, E100° 00.605′). In this specimen, which is a large individual with a frontal width at the interorbital slot of 81 mm, the scales have an average diameter of 2.4 mm. The skin impression was recovered from the thoracic region of the body, although the damage done to the specimen makes it impossible to know exactly which region it covered.Other tyrannosaurid (Albertosaurus, Daspletosaurus, Gorgosaurus) skin impressions have been recovered from Alberta and Montana, and show the same lightly pebbled surfaces. — Currie et al. 2003 p: 6

In one quick paragraph, Currie et al. briefly describe the scale impression found in Tarbosaurus, and say that it looks similar to multiple, undescribed scale impressions from three other tyrannosaurids. Prior to the landmark work of Bell et al., this was the best description of tyrannosaurid integument ever published.

Lastly, we have a “description” of scale impressionsin Daspletosaurus, by Currie and Koppelhus 2015:

Skin impressions associated with tyrannosaurid bones were first found when the holotype of Gorgosaurus libratus (CMN 2120) was being prepared further in the 1980s in Ottawa. Subsequently, skin (TMP 1994.186.0001) was identified with an Albertosaurus from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Edmonton. Traces of skin were found in the field with a large skeleton of Daspletosaurus (TMP 2001.036.0001, Fig. 2), and looked remarkably like that of Tarbosaurus from Mongolia (Currie et al. 2003). Unfortunately, although the skin impressions were collected, recent attempts to find them in the TMP collections were unsuccessful, suggesting they may still be in an unprepared block of matrix. Similar skin impressions (TMP 2003.045.0088) were found in the Albertosaurus bonebed (TMP locality L2204) and are currently under study. — Currie and Koppelhus 2015 p: 621

Once again, we learn of multiple integument impressions for different tyrannosaurids, all mentioned in a cursory examination of the material. No real description given, just a half-hearted mention of similarity to scale impressions that were briefly described in a paper from twelve years earlier.

Of the five species described by Bell et al. in their paper, three are being described for the first time, and all are being thoroughly described for the first time.

(2) These impressions look no different than a rhinoceros ass / plucked chicken / dirt

This argument tends to crop up a lot whenever someone mentions scale impressions in dinosaurs. Often not far behind is this ever so photogenic shot from the rear end of a rhinoceros.

Opponents to the scaly dinosaur idea seem to be real fond of rhino skin, and I can understand why. On the outset, rhino skin has a superficial resemblance to scales. However, if one does a side by side comparison between rhino skin and scales, the differences becomes very noticeable.

As I mentioned earlier, scales have serial homology. That is, each scale looks the same as its neighbours (within reason). That means one should be able to pick out a consistent pattern in scales that won’t be present in cracked skin. So compare the above to these shots from scaly animals:

Compare the above image, with the rhino skin. Note how one can easily see the patterns in the scales (with patterns on top of patterns in some instances), but the rhino skin is more like finding faces in clouds. Yeah, some of the cracks seem similar, but they aren’t near each other and what patterns that do appear, seem erratic. In contrast, the reptile scales have an almost “factory stamped” look to them. Another noticeable difference is in the sharp borders seen between each scale. Compare that to the very diffuse borders seen in the skin of the rhinos above.

Paleontologist, In Sung Paik, provided a set of criteria to determine scales from other biological / geological structures (Paik et al. 2010). These criteria were:

- Pattern — Dinosaur scales show interlocking polygons in a regular pattern

- Contact & interlocking state— Edge-to-edge contact typically found in scales (more distant contact possible if patterned)

- Edge shape — Dinosaur scales show pointed edges (i.e., each scale is distinguishable from the next)

- Internal microfabric of the scales — Scales show an internal microtexture to them (dependent on degree of preservation)

We can see that the three reptile scales above fit these criteria, whereas the rhino skin imprints do not.

Another clear sign that the impressions found for these tyrannosaurids, are likely scales, comes from the detailed description by Bell et al. on the integument impressions of Albertosaurus sarcophagus.

Most notable, however, is a specimen of Albertosaurus sarcophagus (TMP 1994.186.0001) that preserves evidence of feature scales on the abdomen. The feature scales are conical (7 mm in diameter, 2.5 mm high) with radial corrugations and are embedded in a patch of pebbly, circular to hexagonal basement scales (diameter range = 1.4–2.5 mm; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a–d).

You don’t get feature scales on naked skin. It just doesn’t happen.

So yeah, the whole “naked, wrinkly skin” argument doesn’t really work for these integument impressions.

Okay, so what about the other go-to argument? How much do tyrannosaurid skin impressions resemble a plucked chicken?

I have to admit, I don’t get it. If we use the criteria from Paik et al. 2010, we can see that a plucked chicken does satisfy criteria one, in that the plucked areas do show a distinct pattern. However, everything falls apart after that, as feathered areas do not show any type of interlocking polygonal pattern. Instead, the plucked areas look more like raised ridges of skin, which they essentially are. Further, chicken feathers, like those of all birds [most birds], grow in distinct tracts. This is quite prominent in the image to the right, where one can see the feathers taking up distinct sections of the skin, with other areas being completely devoid of feathers. If we were seeing this scenario in tyrannosaurids, we might expect to see large smooth areas of skin between feather tracts. This would be all the more likely if the filaments seen in early coelurosaurs represented protofeathers.

Of course, it’s also possible that the limitation of feathers to distinct regions of the body happened later in avian evolution [note: ratites do not show feather tracts, suggesting that this may be more of a neognath synapomorphy]. Evo-devo work does indicate that featherless regions of the body can be induced to form feathers without much effort (Dhouailly 2009), and a recently accepted manuscript describing a young enantiornithine trapped in amber, does suggest that early bird lineages did have more feathers than extant birds (Xing et al. 2017, accepted manuscript), so the possibility remains that protofeathered dinosaurs did not limit their protofeathers to distinct tracts.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that we still do not see any interlocking pattern with pointed edges, nor any scale-like microtexture. In fact, the texture in bird skin is pretty much completely smooth.

There is another problem with the “plucked chicken” argument. It requires that the animals get denuded prior to burial. The chicken shown in the image to the right is not normal. A filament-covered theropod that dies in a fossil-preserving situation is unlikely to have the exposure time necessary for filaments to slough off, and if it does, we would expect to see some type of folds or wrinkles associated with the sloughing. Another thing to consider is the remarkably thin skin of birds (Pass 1995), which would make plucked skin even less likely to preserve, much less show any type of texture. Lastly, even if an animal like Wyrex or Daspletosaurus did have its integument preserved in this weird fashion, it would be an incredibly rare find, and not one that would likely be repeated in other tyrannosaurid integument impressions.

So the plucked chicken idea doesn’t really hold water.

Laslty, we have dirt, or other simple sedimentological structures.

At first glance, these structures certainly have the most potential to be mistaken for scales. They have a tight interlocking polygonal pattern just like dinosaur scales, but the individual polygons are still randomly arranged. They also lack any fine microtexture to them, since they are just mud. Nontheless, the potential to be confused with scales is still pretty strong here. Paik et al. 2010 even mentioned this potential confusion and cautioned that some published accounts of scales may in fact be other biological or geological structures. Thankfully, the biggest worry of confusing these structures with scales happens when the scales are found in isolation. None of the specimens described by Bell et al. 2017, were found in isolation, save for the Daspletosaurus scale impressions, and even that is a maybe. Given that the specimen that these impressions came from (TMP 2001.036.001) is currently missing, it is hard to determine whether these scales were found in isolation or not. Still, that is only one of five different specimens, and even then the scalation appears to fit the description of the other tyrannosaurids.

So the argument for sedimentological structures, while important to consider, can likely be ruled out due to the proximity of the scales to underlying bones, as well as the feature scales found in A. sarcophagus.

(3) The authors are making blanket statements based off coin-sized samples of “skin”

While I am the first person to jump on a paper for making broad statements that extend beyond the data, I do not think that this accusation is warranted in this case. The authors set out to first describe the shape and distribution of scales in tyrannosaurids. The most I can fault them for is their use of Tyrannosauroid in their paper title. However, I suspect this had more to do with incorporating Dilong paradoxus and Y. huali more than anything else.

I have also heard complaints that the authors didn’t bother to describe the integument found in D. parodoxus and Y. huali, but to that I would say: read the original papers. Both Xu et al. 2004 and 2012, went into as much detail as possible in their descriptions of the filaments found in these two taxa. A further analysis from the authors would not have added much to the conversation.

In contrast, scales have always been given the short end of the stick when it comes to popularization and description. Phil Bell and colleagues represent a new guard of paleontologists that realize that scales were an equally important, if not more important aspect of many dinosaur lives. The work by Bell et al. 2017 stems from previous work on hadrosaurs that included the first ever classification of scale terminology in dinosaurs (Bell 2012), including their use as diagnostic tools for species identification. This attention to detail on scale morphology made these authors the ideal paleontologists to tackle tyrannosaurid integument in a way that removes much of the worry about accidentally assigning scales to non-biological structures.

As for the “coin-size” argument, for that I would like to turn your attention to the incredible work done by Joshua Ballze and company. While it’s true that the combined total for these scale impressions is still pretty small by tyrannosaurid standards, they are a far cry from being just “coin sized”, or even laptop sized pieces of integument.

Further, in spite of their small overall size, these skin impressions represent almost every major part of the body. Thus, when Bell et al. argued that tyrannosaurids were likely scaly all over, it is based on the reasonable assumption that the scales on the tail met up with the scales on the legs, belly, abdomen, neck, and head. This is not extending one’s interpretations beyond the data, but rather using reasonable assumptions and applying them to known integument distributions in these taxa.

Another important aspect to consider is that the authors took their work a step further and performed an ancestral character reconstruction based on known integument distributions in tyrannosauroids. They found that scaly tyrannosaurids (i.e., devoid of any filaments) have a 97% probability of being true, despite an 89% probability that tyrannosauroids started off filamented. The authors arguments for why tyrannosaurids would revert back to scales are interesting and worth pursuing. For instance, if the reversion was driven by body size, then why did Y. huali retain its shag, whereas similarly sized A. sarcophagus was scaly? If climate was responsible for shaggy retention in Y. huali, then why did A. sarcophagus, and Daspletosaurus not retain filaments in their equally “cool” environments?

More importantly, why should scales re-evolve at all? Why not just bare skin? Hopefully this study will encourage others to look into why scales evolved in the first place, and actually test some of their functions rather than stick with the party line of “water retention” and “abrasion protection”.

Some notes on scale size

It’s worth discussing the size of the scales found in tyrannosaurids. Namely, that the scales are remarkably small. The average scale size from all the specimens studied by Bell et al., is ~2.2 mm (range: 1–4.9 mm, not counting feature scales). For reference, this link provides examples of millimeter-sized everyday structures. So we are talking about some remarkably tiny scales. The small size of these scales are what lead paleontologists like Phil Currie, to state that tyrannosaurids were truly naked (i.e., scaleless). So, although tyrannosaurid integument impressions show scales, the scalation in tyrannosaurids would have been remarkably fine.

All that said, a comparison with other dinosaur groups suggests that fine scalation is actually pretty common place within Dinosauria.

The stegosaur, Hesperosaurus mjosi, preserves scales that range from 2–7 mm in diameter (Christiansen et al. 2010), whereas Gigantspinosaurus sichuanensispreserved slightly larger scales at 5.7–9.2 mm (Xing et al. 2008). Ankylosaurids are known for their incredibly well-developed osteoderms, but well-preserved specimens also show that these osteoderms were surrounded by much smaller basement scales that ranged from 1.3–5 mm in animals like Pinacosaurus grangeri (Gilmore 1933) and an undetermined ankylosaur (Arbour et al. 2014). Hadrosaurs are certainly the most common dinosaurs to have presrved integument (Davis 2012), yet even in this group the basement scale range is still small at 1–10 mm in diameter (Bell 2012). Even sauropods, despite their immense sizes, are known to preserve remarkably small scales, such as the small (1–3 mm diameter) type II (= basement) scales in Tehuelchesaurus benitezii (Gimenéz 2007), as well as another indeterminate sauropod with 1–2 mm width basement (Foster & Hunt-Foster 2011). It appears that basement scales in dinosaurs were pretty conservative in size between taxa. Feature scales vary much more and could reach up to 102 mm (Sternberg 1925), before accounting for osteoderm scutes. Yet even here, the few preserved feature scales in A. sarcophagus, fall within the minimum size range for hadrosaurs like Saurolophus osborni (Bell 2012).

Compared to other dinosaurs, tyrannosaurids fall on the low end of average. I suspect that the rather small individual samples that we have may also be biasing our interpretations in tyrannosaurids. As at least one A. sarcophagus specimen shows, there was regional variation along the body. Unfortunately, without a true tyrannosaurid mummy, we won’t know just how varied these scale patterns were in this group.

I suspect that crocodile scutes and ceratopsian skin impressions may be skewing public perception of what dinosaur scales should look like. In crocs, very large scales predominate the dorsal and ventral aspects of the body, whereas ceratopsian scale impressions tend to be dominated by large (5 cm or more) scales (e.g., Sternberg 1925), though even in Ceratopsia, basement scales still tend to remain pretty small at around 3.2 mm in diameter (Davis 2012, supplemental table).

These large scales, along with the fact that many dinosaurs were very enormous animals, tends to skew our perceptions towards large-scalation in large dinosaurs. Looking at the data, however, suggests that large scalation was more limited to specific taxa and specific scale types (i.e., feature scales). Many dinosaurs appear to have grown large while maintaining fairly small scales.

This pattern is more consistent with what we see in lepidosaurs than crocodylians. Compare, for instance, the scale size in land iguanas (Conolophus, Gentile and Snell 2009) or reticulated pythons (Python reticulatus, Auliya et al. 2002). Both are large animals in their respective lineages, yet their scale sizes (aside from head scales) remain remarkably small.

I think we tend to see lizard scales as larger than they are because many detailed lizard pictures are taken up close. Case in point is the study from earlier this year on a new species of fish-scaled geckos (Geckolepis). The pictures in the original paper (Scherz et al. 2017) and associated news articles, makes the animals appear much larger than they are. In the images, the new species, Geckolepis megalepis, is shown wearing a seemingly oversized coat of scales. Yet, reading the paper we find that the largest scales found on the species were 5.8 mm long, which is smaller than the feature scales on A. sarcophagus. What’s nearly indescribably tiny on a tyrannosaurid, is almost 10% of the snout vent length on this little gecko.

It would be interesting to see how scalation changes with body size, but to date no one has studied this. It’s likely contingent on phylogeny (you use what you have), but I wouldn’t be surprised to find that scale count, rather than scale size, increases with body size in lepidosaurs and dinosaurs.

Enfluffening the gaps

Lastly, I want to talk about the other thing I have noticed in relations to these papers. I saw this pop up a little bit with the Carr et al. paper, and a whole lot with the Bell et al. paper. Opponents to the idea of scaly tyrannosaurids argue that , even if the scales found on the body / face are true:”They could still have feathers on the back / between the scales / when they were young“.

This argument reminds me a lot of the God of the Gaps argument used in creationism vs evolution debates. This argument proposes that anywhere where science lacks sufficient knowledge of something, that is where god lies. The problem with this approach is that as science explains more and more of the natural world, the influence of god on nature gets pushed more and more to the periphery. Thus, god just becomes a placeholder for areas that we currently don’t know. We appear to be seeing similar arguments being put forth for the presence of filaments in dinosaurs.

I’ve heard it argued for sauropods, despite embryonic remains showing scales. I even seen it used on ornithopods, despite near complete scaly mummies. Now, with tyrannosaurids, this “enfluffening the gaps” is being proposed for the back of the animals (the only area that we lack integument preservation) and for hatchlings.

Points to the authors, Bell et al. do tackle these enfluffening arguments in the original paper.

Combined with evidence from other tyrannosaurids…provides compelling evidence of an entirely squamous covering…suggesting that most (if not all) large-bodied tyrannosaurids were scaly and, if partly feathered, these were limited to the dorsum.

…

Finally, the presence of epidermal scales in a large adult individual does not rule out the possibility that younger individuals possessed feathers—a developmental switchover that, to our knowledge, would be unprecedented at any rate.

This line of reasoning essentially echoes what I have written before. Ontogenetic shifts in integumentary appendage type does not happen in any extant animal. As such, proposing that it happened in dinosaurs constitutes an extraordinary claim that would require extraordinary evidence. As for that infamous feathered mohawk trope, I have also expressed my problems with that argument before.

Conclusions

These two new papers on tyrannosaurid integument were a long time coming, and regardless of one’s take on the data, it is great to see these specimens get a real description. That both papers have received such heated interactions will hopefully spur other paleontologists to look for more soft tissue specimens, and even do some ultrastructural analyses of preserved scales to see how much of the origiinal morphology survived. Who knows, maybe one day we will finally find that elusive tyrannosaur mummy.

Regardless, the data presented in these two papers certainly indicates that scales are important integumentary structures that warrant the same level of scrutiny and analysis that filaments have been getting since 1996.

~ Jura

References

Arbour, V.M., Burns, M.E., Bell, P.R., Currie, P.J. 2014. Epidermal and Dermal Integumentary Structures of Ankylosaurian Dinosaurs. J. Morphol. 275(1):39–50.

Auliya, M., Mausfeld, P., Schmitz, A., Böhme, W. 2002. Review of the Reticulated Python (Python reticulatus Schneider, 1801) with the Description fo New Subspecies from Indonesia. Naturwissenschaften. 89:201–213.

Barker, C.T., Naish, D., Newham, E., Katsamensi, O.L., Dyke, G. 2017. Complex Neuroanatomy in the Rostrum of the Isle of Wight Theropod Neovenator salerii. Scientific Reports. 7:3749.

Barrett, P.M., Evans, D.C., Campione, N.E. 2015. Evolution of Dinosaur Epidermal Structures. Biol. Lett. 11:20150229.

Bell, P.R. 2012. Standardized Terminology and Potential Taxonomic Utility for Hadrosaurid Skin Impressions: A Case Study for Saurolophus from Canada and Mongolia. PLoS One. 7(2):e31295.

Bell, P.R., Campione, N.E., Persons, W.S., Currie, P.J., Larson, P.L., Tanke, D.H., Bakker, R.T. 2017. Tyrannosauroid Integument Reveals Conflicting Patterns of Gigantism and Feather Evolution. Biology Letters. 13:20170092.

Brusatte S.L., Carr T.D. 2016 The Phylogeny and Evolutionary History of Tyrannosauroid Dinosaurs. Scientific Reports 6:20252.

Carr, T.D., Varricchio, D.J., Sedlmayr, J.C., Roberts, E.M., Moore, J.R. 2017. New Tyrannosaur with Evidence for Anagenesis and Crocodile-Like Facial Sensory System. Scientific Reports. 7(44942):1–11.

Christiansen, N.A., Tschopp, T. 2010. Exceptional Stegosaur Integument Impressions from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Wyoming. Swiss. J. Geosci. 103(2):163–171.

Currie, P.J., Badamgarav, D., Koppelhus, E.B. 2003. The First Late Cretaceous Footprints from the Nemegt Locality in the Gobi of Mongolia. Ichnos. Vol.10:1-12.Currie, P.J., Badamgarav, D., Koppelhus, E.B. 2003. The First Late Cretaceous Footprints from the Nemegt Locality in the Gobi of Mongolia. Ichnos. Vol.10:1-12.

Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B. 2015. The Significance of the Theropod Collections of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology to our Understanding of Late Creataceous Theropod Diversity. Can. J. Earth. Sci. 52:620–629.

Davis, M. 2012. Census of Dinosaur Skin Reveals Lithology May not be the Most Important Factor in Increased Preservation of Hadorsaurid Skin. Acta. Paleo. Polo. 59(3):601–605.

Foster, J.R., Hunt-Foster, R.K. 2011. New Occurrences of Dinosaur Skin of Two Types (Sauropoda? and Dinosauria indet.) from the Late Jurassic of North America (Mygatt-Moore Quarry, Morrison Formation). J. Vert. Paleo. 31(3):717–721.

Gentile, G., Snell, H. 2009. Conolophus marthae sp. nov. (Squamata, Iguanidae), A New Species of Land Iguana from the Galápagos Archipelago. Zootaxa. 2201:1–10.

George, I.D., Holliday, C.M. 2013. Trigeminal Nerve Morphology in Alligator mississippiensis and its Significance for Crocodyliform Facial Sensation and Evolution. Anat. Rec. 296(4):670–680.

Gilmore, C.W. 1933. Two New Dinosaurian Reptiles from Mongolia with Notes on Some Fragmentary Specimens. Am. Mus. Nov. 679:1–20.

Gimenéz, O.V. 2007. Skin Impressions of Tehuelchesaurus (Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Patagoinia. Rev. Mus. Argentino Cienc. Nat. n.s. 9(2):119–124.

Hieronymus, T.L., Witmer, L.M., Tanke, D.H., Currie, P.J. 2009. The Facial Integument of Centrosaurine Ceratopsids: Morphological and Histological Correlates of Novel Skin Structures. Anat. Rec. 292:1370–1396.

Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P.C., Dal Sasso, C., Maganuco, S., FAbbri, M., Martill, D.M., Zouhri, S., Myhrvold, N., Lurino, D.A. 2014. Semiaquatic Adapations in a Giant Predatory Dinosaur. Science Express. 345(6204):1613–1616.

Milinkovitch, M.C., Manukyan, L., Debry, A., Di-Poi, N., Martin, S., Sing, D., Lambert, D., Zwicker, M. 2013. Crocodile Head Scales are not Developmental Units but Emerge from Physical Cracking. Science. 339:78–81.

Paik, I.S., Kim, H.J., Huh, M. 2010. Impressions of Dinosaur Skin from the Cretaceous Haman Formation in Korea. J. Asian Earth Sci. 39:270–274.

Pass, D.A. 1995. Normal Anatomy of the Avian Skin and Feathers. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine.4(4):152–160.

Scherz, M.D., Daza, J.D., Köhler, J., Vences, M., Glaw, F. 2017. Off the Scale: A New Species of Fish-Scale Gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Geckolepis) with Exceptionally Large Scales. PeerJ. 5:e2955.

Sternberg, C.M. 1925. Integument of Chasmosaurus belli. Canadian Field Naturalist. 39:108–110.

Tellez, M., Paquet-Durand, I. 2011. Nematode Infection fo the Ventral Scales of the American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) and Morelet’s Crocodile (Crocodylus moreletti) in Southern Belize. Comp. Parasitol. 78(2):378–381.

Witmer, L.M., Ridgely, R.C. 2009. New Insights into the Brain, Braincase, and Ear Region of Tyrannosaurs (Dinosauria, Theropoda), with Implications for Sensory Organization and Behavior. Anat. Rec. 292:1266–1296.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J.K., McKellar, R.C., Chiappe, L.M., Tseng, K., Bai, M. 2017. A Mid-Cretaceous Enantiornithine (Aves) Hatchling Preserved in Burmese Amber with Unusual Plumage. Gondwana Research. Accepted manuscript.

Xing, L., Peng, G., Shu, C. 2008. Stegosaurian Skin Impressions from the Upper Jurassic Shangshaximiao Formation, Zigong, Sichuan, China: A New Observations. Geol. Bull. China. 27(7):1049–1053.

Xu, X., Norell, M.A., Kuang, X., Wang, X., Zhao, Q., Jia, C. 2004. Basal Tyrannosauroids from China and Evidence for Protofeathers in Tyrannosauroids. Nature. 431:680–684.

Xu, X., Wang, K., Zhang, K., Ma, Q., Xin, L., Sullivan, C., Hu, D., Cheng, S., Wang, S. 2012. A Gigantic Feathered Dinosaur form the Lower Cretaceous of China. Nature. 484:92–95.

Amazing Article! Great to have Scaly T-rex scientific, again!

“More importantly, why should scales re-evolve at all? Why not just bare skin? Hopefully this study will encourage others to look into why scales evolved in the first place, and actually test some of their functions rather than stick with the party line of ‘water retention’ and ‘abrasion protection'”

Maybe, once the tyrannosaurids lost their ancestral plumage, scales took over to protect the skin from sunburn? I am not sure how UV radiation levels would have compared between today and the Cretaceous, but if their hides ever went through a “naked” phase, I think a scaly covering could block out harmful UV rays. Of course, this wouldn’t have happened in any lineage of mammals since (if I recall correctly) they never had reptile-style scales in their ancestry. Although I admit I am not sure whether a “naked” phase ever existed in tyrannosaur evolution; alternatively, they could have instantly “switched” from filaments to scales. What are your suggestions?

I think you may be onto something there. I had not considered UV protection before, but it does make sense. Avigdor Cahaner’s infamous featherless chickens seem to pass out when exposed to direct sunlight, which strongly indicates that the skin by itself has lost all UV protective abilities. Bauer and Russell (1992) suggested something similar for the underlying skin in geckos that have evolved regional integumentary loss (skin sloughing). Apparently some species show pigment cells in the deepest layers of the skin whereas others do not. The authors argued that the nocturnal habits of these geckos may offset any potential UV damage caused during integument regeneration. Unfortunately, that’s about all there is out there. The only real studies on scaleless reptiles were one that tested the role of scales in heat transfer and water loss (Licht & Bennett 1972), along with the recent paper on scale formation in bearded dragons (Di-Poi & Milinkovitch 2016). This remains a rife area for study.

Refs

I think you should comment on how small the actual scales are. I believe they are described as being 1-2 mm in diameter for the most part. 2mm dia is probably the size of the black space inside of one the O’s in this sentence. Additionally, for the feature scales 6mm is about as wide as the M’s in mm. All of those sizes are much smaller than what are on the body of the iguana. The animal in the image above is probably close to life sized. It is kind of misleading showing images of the tyrannosaur scales looking gigantic in the images when they are quite tiny. I buy the naked Rex idea, but I get the distinct feeling people are trying to push back into spiky death monster territory.

You’re right. I should have delved more into the size of the scales themselves. Initially, I wanted to point out that””contrary to popular opinion””we actually do have a fair amount of body covering for tyrannosaurids. In my haste, I forgot to talk about the size of the scales themselves. Initially I was going to go into detail in this comments, but I think it would be better to add it to the original post.

And yeah, I agree, we should keep the pendulum from swinging back towards scales = monsters territory.

A well written and concise summary that should be widely read. However (and you know that was coming) my qualms are as follows 1) In the Hieronymus paper – which is a must read as it does the “heavy lifting” for the Carr paper – they assert that nekkid skin (as in modern birds) can not produce a hummocky texture on bone. I would dispute this on the observation that phorusrhacid skulls – presumably nekkid flesh and not scaly – have a hummocky texture: http://dinoanimals.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Phorusrhacos-2.jpg Furthermore I am a bit leery of the conclusions that Carr makes concerning facial appearance because A) the obvious mistake that should have been caught in peer review pertaining to cracked croc skin & lack of scales does not inspire much confidence B) Lots of other animals besides crocodile have a similar skull texture but are not necessarily scaled or tight skin Behind Your Bony Mask of FaceC) The Hieronymus paper dealt with Pachyrhinocerous very well but I am not convinced that the work translates to a theropod ( which we now know) had a rather complicated integumentary history of scales-feathers-scales

There is an oversight in your characterization of the Wyrex scales in this post as showcasing pattern and regularity. Some of the other tyrannosaurid scales do show pattern and regularity the “factory made” design you mention. But not the Wyrex scales. Indeed if you read the description from the Bell paper they say so themselves “Individual scales are higly variable in shape ranging through elongate, elliptical, sub rectangular, and irregular three to six sided polygons”. So, yes, there are “factory made” scales within some of the specimens in question – the Wyrex “scales” are not of that gestalt. In fact, given the globular and small size (1mm<) I would best approximate these structure to the fine quasi scale structure of some example of carunculate skin i.e. chicken combs. I wrote of this in my blog post in addition to providing some compelling photo comparisons which do illustrate a startling morphological similarity to the irregular Wyrex "scales" and carunculate skin.

An Issue of Scale

Again, thanks for an excellent summary and great observations and points

Duane Nash

Hi Duane,

Thanks for the response. I looked at the phorusrhacid skull you showed and its hard to see if there really is a hummocky texture there. I’m assuming you are referring to the rostral end of the beak where we see some well-defined rugosity. The trouble is that all the rugosity we can see with our naked eye looks practically the same. Hieronymus’s work on rugosity profiles required microscopic and histological examinations, which we really can’t see with a typical photo.

For instance, as you mentioned, crocodylian rugosity and hippo rugosity look very similar on the surface. However, Hieronymus et al. gave a pretty in-depth description of hippo bone texture and they found that hippos show a projecting rugosity profile in which each projecting peak represented areas of metaplastic ossification between the bone and the surrounding collagen (see Hieronymus et al. 2009, figure 8E). I wish the authors had offered a similarly in-depth look at croc bone, rather than lump them in with squamates. On the bright side, we can get some idea of what the bone histo was like thanks to the recent work by de Buffrénil et al. (2015). It seems to have more of a projecting rugosity profile rather than the hummocky profile we see in iguanians (the caveat being that de Buffrénil et al. focused on the “ornamented” parts of the skull and osteoderms, rather than near the teeth, where things may be different).

In the case of the phorusrhacid beak, if it follows suit with what we see in other birds as well as turtle beaks, the profile should show that same projecting rugosity profile. That phorusrhacid beaks seem particularly rugose is likely a sign that they were used in high impact scenarios that required extensive reinforcement. I suppose, in the end, comparing the tyrannosaurid skull texture to crocs was probably a mistake.

Regarding the scales in Wyrex, you raise a good point about the variability mentioned in the Bell et al. paper. They do mention that individual scales show quite a bit of variation between each other, and that is cause for pause when it comes to assigning them to epidermal scales. The scales (or alleged scales) do still have well-defined, “sharp” borders, though, which helps, and as you mentioned the other scale material from tyrannosaurids seems to better fit the “factory stamped” pattern, so there is still that. Nonetheless, it does leave me with questions about what was up with Wyrex (potential preservations weirdness?). I might contact the authors to get more info on this.

It also worth noting that the best preserved patch (at least as far as I’ve seen) comes from the neck (it’s the piece shown in the image in this blog post, as well as the most commonly cited image of Wyrex scales), where the variation is much reduced, as Bell et al. write:

On a side note, it’s worth noting that the diameter of these scales may be small, but since the scales are not equilateral, the overall size of the scales is larger than the text leads us to believe. Looking at the Wyrex neck scales, and using the scalebar provided, their length seems to be between 1.5—2 mm. Some may be even longer than that, but it gets harder to tell where one scale ends and another begins in the photo provided.

All that said, I take your point. A bit more consistency in the scale pattern in Wyrex would have been nice. I wish Bell et al. had provided higher resolution figures for a lot of their descriptions. I suspect that limitations from the publication are to blame for that, though (even PLoS is stingy about image size). The comparison to carunculate skin is certainly interesting. I don’t quite see the similarities you do, but I admit it would be worthwhile to explore this area further and see what these structures look like on a more ultrastructural level. Hopefully that is something that Bell et al. are considering in the future for any dinosaur scales (seriously, can we at least get one?).

Additional reference

Amazing article as always, interesting to read all the research, that’s finally showing up these days.

BTW, regarding feathered skin structure, here is a recent article by Scott Hartman on Anchiornis…

http://www.skeletaldrawing.com/home/anchiornissofttissue

Thanks, I remember giving Scott’s post a read a while back along with the original paper. It’s certainly interesting, and somewhat surprising, that reticulae were found on the hands of Anchiornis huxleyi. This suggests that pennaraptorans still used their hands for something (probably climbing). That we have the well-defined footpads is awesome too. As for the dorsal foot / tibial stuff, I’m more skeptical. The authors themselves are cautious in their interpretations here, due to the preservation. They might be scales, or they might be bare skin. The details are just not there. Regardless, it sounds like all of these “scales” are reticulae (i.e., aborted feathers), which makes sense given the extensive feather covering. They also seem to be distal to the feathers on the hind limb, rather than interspersed, which agrees well with the distal-to-proximal direction hypothesized for scale re-evolution in birds (Zheng et al. 2013). Regardless, it remains an amazingly preserved specimen and gives us an incredibly in-depth look at what A. huxleyi looked like in life.

Additional Reference

Hi, Hope your doing well. here’s a more recent diagram by Joshua Ballze.

Another more updated version is coming soon as well.

https://www.deviantart.com/blomman87/art/The-Newest-updated-version-Tyrannosaur-skinchart-748376293

Hey folks,

I’m glad to see the posts has been getting some exposure. I just finished an intense interstate move for my new job, so I apologize for the delay in getting back to folks. I’m slowly working on responses now.

As an aside, how do you think tyrannosaurids may have shed their skin? I read that while lizards shed their skin in patches, crocs shed individual scales inside. I am inclined to think tyrannosaurid shedding was more like that of lizards since their scales appear to be small and fine rather than big like crocodiles’.

The large scale-patch style of molting that we see in today’s lizards and snakes appears to be a trait unique to Squamata, and possibly Lepidosauria (though Tuataras do things a bit different). Lepidosaurs have a special layer of epidermis called the oberhäutchen layer. In squamates, this layer serves as the shearing surface that lets the scales shed en masse. We don’t see this layer in any other reptile groups, nor in birds, making it pretty likely that this was a lepidosaurian or squamate novelty.

So, although tyrannosaurids did show smaller scales than those we see in extant crocodylians, they probably still shed them in a manner more akin to dandruff than what we see in lizards and snakes.

While I’m glad to know there are criteria you can check to see if an impression is likely truly scales or not, there is something I’d like to point out.

That chart. It has problems. Some of these impressions are in unknown locations, and thus putting them on a clear part of the body is misleading. And the neck impression found by Detrich (https://www.facebook.com/bob.detrich/posts/756344754401099) and (http://cjonline.com/stories/101801/kan_trexskin.shtml#.WTLqGrT3ahA) described as more like elephant skin or plucked bird skin by Currie. And none of the Bell et al authors helped with that chart.

“This line of reasoning essentially echoes what I have written before. Ontogenetic shifts in integumentary appendage type does not happen in any extant animal. As such, proposing that it happened in dinosaurs constitutes an extraordinary claim that would require extraordinary evidence”. Some birds do, in fact have Integumentary changes during ontogeny and even during seasonal changes. Ptarmigans have feathered feet in winter and scaly feet in summer (however I’m not sure if the feathers are growing between the scales then fall of, or if the scales fall off and feathers grow in place then scales regrow, or if reticulae actually turn into feathers). Some owls do, in fact, grow more filaments on their feet when growing older (http://105697.deviantart.com/journal/Tyrant-Tantrums-Part-II-Skin-n-Feathers-n-Scales-687705922). Mark Witton mentions that bird skin is quite dynamic and integumentary changes during ontogeny do happen (http://markwitton-com.blogspot.co.uk/2017/06/revenge-of-scaly-tyrannosaurus.html). Filaments do grow in between scales, so even if Tyrannosaurids were completely scaly as adults the young could still conceivably be feathered for insulation purposes. (Remember, ontogeny replicates phylogeny, sometimes). And the “feathers in the gaps” arguments….I don’t see what’s wrong with that? Kulindadromeus, Juravenator, Anchiornis, the Burmese amber Enanthiornithine, Caudipteryx (scaly/naked fingers). Scales and filaments (whether these filaments be homologous to bird feathers or not) can and did coexist. Perhaps the common ancestor of Ornithodira was fully filamentous and many of its descendants evolved scales/stunted feathers secondarily? This was suggested by commenter David ÄŒerný a while back. Your argument about ontogeny I have said above. I hope I don’t come accord as biased. If Tyrannosaurids were completely scaly that’s great. We will be learning more about dinosaurs which is great. But at the moment I doubt it.

Being skeptical is always welcomed. I think we all benefit from maintenance of skepticism in many areas of paleontology. The issue of integumentary types in tyrannosaurids is particularly interesting given their position among theropods, so an extra layer of skepticism both ways is probably a good idea.

Regarding Josh Ballze’s diagram, I can understand the skepticism given that it wasn’t done for a professional publication, nor was it done by any members of the Bell et al. crew. If it helps, the illustrator did go through extensive revisions with multiple paleontologists, including Dr. Carr, and he did talk with Mr. Detrich to nail down the anatomical location of his undescribed impressions. Areas that come from unknown locations are also marked as such, making it a pretty detailed compilation of all the officially known pieces, and one that shows the illustrator did his homework (more can be read on it here).

Regarding the ontogenetic shifts, I’ve not heard of owls getting fuzzier as they get older. I know that older individuals tend to mineralize their foot tendons (personal observation), but I’ve not seen much info on feathering changing with age. Are there any images or references I could look at for that? It would be interesting to follow up on (owls in general, are an interesting group for integument). Regarding the ptarmigans, I thought I had written about them before, but apparently I only did so in passing (regarding their after-feathers). You’re right that the feathery feet are contingent on the time of year, but the catch is that they don’t have scales in the summer. They just have naked feet, as shown here. The lumpy bits on the feet are dermal papillae, which are likely where the feathers are growing out of. So they do drop their feathers in the summer, but they don’t replace them with anything.

I remember reading Mark’s blog post a while back and reading his take on bird skin being dynamic. I don’t completely agree with his statement that reptile scales can’t be forced to grow feathers. Dhouailly (1975) did some dermo-epidermal recombinations that showed reptile (lizard) epidermis was capable of “trying” to make feathers (it forms a series of scale-like buds in the same arrangement as feathers). I also can’t quite see where the references he cites support the ever changing integument position. Lennerstedt talked about papillae, which I believe he meant to be reticulae (at least based on this image), which are those aborted feather buds. Sending some growth hormone to these buds appears to extend them into more mature feathers, but it still doesn’t change the overall integument type. As for Stettenheim (2000), he wrote:

Regarding the scales filaments argument, I have no qualms with saying that filaments may be able to grow among scales, in part because we don’t know the embryology of those filaments. I have a harder time accepting that feathers or their forbearers could, as we have a pretty extensive list of Evo-Devo studies (dating to at least the early seventies) that shows the antagonistic relationship between these two epidermal derivatives. As for filaments being ancestral to Ornithodira, it’s possible, but as I told David in those comments, and in the original post, I don’t think it is the most parsimonious (i.e., scales re-evolving on numerous occasions, vs filaments [of different shapes] evolving a couple of extra times). The paper from Barrett et al. 2015 is currently the only published test of ancestral integument in dinosaurs. It places scales as the likely ancestral integumentary type as well (with notable caveats regarding the sensitivity to what Pterosaurs had).

Hopefully the trend in studies on integumentary types in dinosaurs continues. I’m certain that we’ve only cracked the surface of all this stuff.

Additional references

Of course this doesn’t mean we can slap feathers on all Dinosaurs without a second thought. Environment and phylogeny are large influences on integument.

Many thanks for this post. I especially like “New tyrannosaur scale paper for old tyrannosaur scale imprints” (which covers things I’ve been wondering about for a while). If/when you’re not too busy, I have a few questions:

-To paraphrase Sim Koning, “Some bird species grow thick feathers over their foot scales seasonally [See “FIGURE 1”: https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/condor/v079n03/p0380-p0382.pdf ], and wood storks shed feathers from their necks as they grow scale-like plates in their place [ https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/a1/27/32/a127323f852b74706ef300afb7c386f7.jpg ]”. I’m no expert, so IDK how analogous ptarmigans & wood storks are, but figured they were worth mentioning. What do you think?

-Similar to the above question, what do you make of owl feet ( http://cdn1.arkive.org/media/4D/4D5A9182-30E4-4B2D-9DAD-6D412535277B/Presentation.Large/Close-up-of-barn-owl-foot.jpg )?

-You’ve mentioned Juravenator in previous posts. Will you ever write about it in detail? I ask b/c scaly T.rex skeptics bring it up a lot.

I’ve had the opportunity to work on wood storks and the stuff on their neck is certainly interesting. It’s basically carunculate skin that looks kind of like scales from afar. Up close though, the patterning is very random and diffuse. The skin is also very soft and pliable.

Regarding ptarmigans, see my response to Mr. Crow, two posts up. Ptarmigan seasonal snowshoes are pretty cool, but there is no swapping of integument going on, just the dropping of feathers in the summer. As for owls, I find what is going on with their feet to be pretty interesting. As I mentioned to Dave ÄŒerný in the comment thread for this post, the apparent interaction of filaments with scales intrigues me because owls seem to be doing something that no other bird has been able to do. That the filaments along the feet look very much like hairs, makes me question their interpretation as feathers. I’m currently in the process of collecting some specimens for histological sectioning to see what type of interaction is going on down there. If they do wind up being true feathers, there is a potential means that could explain the interaction, but that will have to wait for another more in-depth post about integument (currently on my list of things to post about).

As for Juravenator starki, I’d love to talk more about the specimen, but there’s not really anything new to add. The last study on the specimen was in 2010. It’s definitely a critter that warrants a more in-depth study, but until someone does that, we are all just stuck with what is currently published.

Something to note: Ratites don’t have their feathers arranged into separate tracts. Neither does Anchiornis (https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms14576).

Whoops, good point. I’ll fix it in the original post.

The “plucked chicken” comparison has always irked me to unbelievable degree, and makes me think that anyone making this claim has never seen a reptile in their life.

A cursory glance through some sites tell me that this new information has been met with quite a bit of skepticism, with some folks bordering on outright denial at the thought of a scaly Tyrannosaurus. That said, I have seen the skin impression compared to caruncles on the heads of chickens. What do you make of these comparisons?

Regarding carunculate skin, as I mentioned to Duane Nash in a previous comment here, I think it’s an interesting hypothesis that is worth further study. I don’t really see the same similarities that Duane does (I think the rugosity in caruncles look much smaller and more diffuse in their shapes), but I definitely welcome more in-depth studies on the histology and ultrastructure of caruncles.

There is evidence for Neovenator (which probably wasn’t aquatic) having a sensitive snout, and more evidence than just the texture of the skull (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-03671-3). Birds too, have sensitive faces.

True, the skin impressions don’t look much like rhinoceros skin. They look much more like scales than rhinoceros skin. But, they also do bear some resemblance to elephant skin. And to the carnucled faces of chickens and black vultures.

Mr Crown, they sure look much more reptilian than elephant or caruncled faces of chickens to me, Tyrannosaurid’s skin resembles the ones of Hadrosaur’s as well, perhaps it was the norm for most dinosaurs, I can’t understand why people compare them to plucked chicken or Rhinoceros skin at all!!

Maybe it’s just me, but the scales don’t look very uniform, as scales tend to be. Then again, bird reticulae aren’t always uniform…

It’s also possible that some of these impressions may be scales, and some may be carnucled skin. It’s also possible that integument varied across the body. It’s also possible that Tyrannosaurids were completely scaly. I’m just throwing possibilities out there.

Good post, lots of interesting material here to think about. I do have one small nitpick to make though. “A filament-covered theropod that dies in a fossil-preserving situation is unlikely to have the exposure time necessary for filaments to slough off, and if it does, we would expect to see some type of folds or wrinkles associated with the sloughing.” This isn’t necessarily true. Feathers, filaments, and fur can come off quite rapidly in the right conditions, and those conditions happen to fit right in with good fossil preservation environments. Carcasses that spend much time in water saturated environments can sometimes get quickly denuded and then buried without showing any folds or wrinkles that one could readily identify with the sloughing, especially if the animal has mange. I’ve seen more than one completely naked dog getting buried in a stream and when I did my ostrich head taphonomy experiments, the feathers flew fast and furiously.

This whole thing is really interesting, but I think you are mistaken about the “filling the gaps” thing (I know I already commented before, but since much more evidence has been brought since the last time I commented here I will comment on this post).

First we have what you said about extant animals not showing such absurdly radical change as they grow: I have to say that, while this is certainly no proof that it happened, saying that we should have actual FOSSIL evidence for this to speculate that some dinosaurs showed this growth pattern is also to exagerate because just because EXTANT animals do not show it it does not mean that it could never happen in extinct animals. What we have to do is compare the development of scales and feathers and see if they are too different for one to replace the other (personally I think this would make a great post in your blog),

I also have issues with one of the main arguments you used to support scaly tyrannosaurids even before this study was shown: you said that if a specific integument is seen on the tail and/or the neck it is a proof that the animal should have the same integument in almost every part of the body since this is a pattern seen in modern animals like birds (forgive me if this is not what you meant, but it looked like you actually meant this… wich must be why Arsen told me the exact same thing). The issue is that this ratiocination ignores the very thing that is the fuel of evolution: mutations, mutations that we can not predict and that may break previously seen patterns. Sometimes we see a clear pattern on a specific group but a specific mutation may break such pattern, and if this does not bring a major disvantage to the animal it endures in the species and sometimes in the group itself. It would be possible for certain dinosaurs to, for example, show primitive feathers on the neck and in the chest but be scaly everywhere else, because this is how evolution works: there is no unbreakable pattern and a characteristic is only diminished if it brings a major disvantage to the animal (this is why we rarely see white tiger and white lions in the wild while white fur is the main reason for the success of polar bears).

As another example about what I said on the previous paragraph: in this post you said that the scakes should look like their neighbors, but the croc photo clearly shows osteoderms (bony scales, that develop differently than “pure” scales) right next to “pure” scales. While these are far more similar to each other than feathers are to scales, they are still different in many aspects.

Is it true that pterosaurs had feathers as this paper says?

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-018-0728-7

It took a while for me to get this one finished, but I recently did a post covering my thoughts on all of this. http://reptilis.net/2021/07/05/were-pterosaurs-naked-after-all/

What’s your take on the paper Dhouailly diid with Godefroit? https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/exd.13391

I find it especiially interesting how they conclude all skin integuments have a common origin with teeth.

I found the paper very interesting, especially the part where the authors push back the origin of all these integumentary appendages to the formation of dermal “teeth” of chondrichthyans. It lines up well to the recent discovery that lepidosaur scales do form placodes (Di-Poi et al. 2016), making their scale formation identical to other reptiles (at least at this basal-most level). It also jibes well with evo-devo work indicating that crocodylians had the genetic toolkit needed to make feathers (Holthaus et al. 2018). Evolution has no qualms with messing around with ancient regulatory genes.

I do contest some of the authors’ interpretations of the dinosaur and pterosaur integument (from what I can tell from my interactions with Dr. Dhouailly, she is taking Godefroit’s interpretation of the data and going from there. No ultrastructure tests yet), but the paper itself is a great review and future reference.

There is an updated “what we know of integument formation” post in the works. It will be taking this new paper into account. I just need to get it finished.

References

Di-Poï, N., Milinkovitch, M.C. 2016. The Anatomical Placode in Reptile Scale Morphogenesis Indicates Shared Ancestry Among Skin Appendages in Amniotes. Science Advances 2(6):e1600708.

Holthaus, K.B, Strasser, B., Lachner, J., Sukseree, S., Sipos, W., Weissenbacher, A., Tschachler, E., Alibardi, L., Eckhart, L. 2018. Comparative Analysis of Epidermal Differentiation Genes of Crocodilians Suggests New Models for the Evolutionary Origin of Avian Feather Proteins. Genome Biol Evol. 10(2):694-704.

A quick question. As a layman, I’m a bit confused about something. Do the evo-devo studies regarding scales/feathers indicate that scales and feathers cannot co-exist on the same animal? Am I correct in that?

The short answer is yes: the two are incompatible, but there are situations that make it seem like it can happen.

The more long-winded answer is that the interaction of integumentary appendages (scales, feathers, and hair) with integument (skin) is complicated. Unfortunately, too many people (including many paleontologists) just read the “scales and feathers can’t coexist” statement and look for some edge case to show it’s not true (notably, birds having scales on their feet).

Evo-Devo studies have shown that the developmental process that makes scales and the developmental process that makes feathers are the same. The feather pathway built off of (hijacked) the scale pathway. This means that you can’t have scales in the same place as feathers because they are both using the same process. Transplant studies from the late ’70s and more recent studies from the ’10s have found that the largest determinant for scale formation in bird legs is how much of the feather signal is present. If you completely obliterate the feather signal you get completely naked animals (i.e., no scales or feathers). The feather formation pathway has to be suppressed but not stopped. When the feather portion of the integument signal is reduced enough, then scales will form (they remain as the underlying signal). This is often misinterpreted as bird scales “evolving from feathers”. They didn’t. The scale formation pathway is still there, it’s just mostly overwritten by the feather pathway. Even a slight increase in the feather-forming signal at any point in leg scale development will mess up the scale forming pathway, leading to the “feathery scales” seen in some chicken and pigeon breeds.

This is also why some owls show what looks like feathers in between their scales. They have very simple filaments that may or may not be true feathers (but still likely a feather variant), popping up at the interface of their scaly tarsometatarsus and the end of their normal feathers, with a weakly diffuse spread of filaments along the rest of the tarsometatarsus. This is the result of turning down the feather signal at the extremities but doing so slower than in other birds (hence the somewhat weird mix).

The owl and chicken/pigeon breed variants have led some paleontologists to speculate that dinosaurs should be able to have feather-scale mixes anywhere, but this speculation ignores how that feather scale mix forms, as well as the fact that birds are only capable of retaining scales on their tarsometatarsus. Transplant studies on other parts of the body have found that the feather-forming signal is just too strong. There is no remnant of the scale forming pathway left.

So, what’s your take on the whole ‘theropods had lips like lizards’ thing?

Your “God in the gaps” comparison is kinda dumb ngl

He mostly nitpicks and doesn’t know the word “Speculation” literally.