For a primer on this blog series and an FAQ see here.

| Other Episodes |

||||

| Coasts | Deserts | Freshwater | Ice Worlds | Forests |

| Islands | Badlands | Swamps | Oceans | North America |

This episode features contributions from the following paleontology consultants:

- Steve Brusatte

- John Conway

- Alexander Farnsworth

- Scott Hartman

- John Hutchinson

- Robert Spicer

- Paul Valdes

- Mark Witton

- Darren Naish

This is the final episode in the series and is another episode that is a potpourri of content. As described in the associated Twitter Megathread, the only overarching “theme” is that it all takes place in North America.

Scene 1: Southern shores of the Western Interior Seaway

As with the Oceans episode, the presence of the Western Interior Seaway (WIS) during the Late Maastrichtian is controversial, but there is enough data out there to argue that it could have been present, which is the position taken by Prehistoric Planet.

Baseless speculation

Alamosaurus with thumb claws

One of the “star” species in this scene is Alamosaurus sanjuanensis. As with Dreadnoughtus schrani from the Deserts episode, we are once again treated to titanosaurs with thumb claws. As discussed in the Deserts episode, this is an incorrect inference of the anatomy and one that Naish was aware during production. He brings up this anatomical flub in the Megathread for this episode, though does not delve into detail as to why this was chosen aside from an incorrect interpretation of titanosaur phylogeny as discussed in the Deserts episode.

The thick hide of Alamosaurus

After the overnight death of an “old” male A. sanjuanensis, the audience is shown a group of nameless troodontids coming across the body and attempting to eat it. Attenborough informs the audience that the three-inch thick hide is beyond their power. We have no skin impression data from A. sanjuanensis nor do we have enough skin impression data to interpret sauropod skin thickness. So, a nearly 8 cm (3 inch) thick hide is based on not much of anything.

Greedy Tyrannosaurus

The next animal to show up on this scene is Tyrannosaurus rex. A single individual (nice change of pace) comes upon the dead A. sanjuanensis and then…chases off the troodontids that are trying to get inside it. This is a weird response for a predator the size of T. rex when dealing with a food item the size of A. sanjuanensis. Typical large predators just come up to a carcass and start eating. Even large crocodiles will do this to a pride of lions for far smaller food items. There is no scaring off other predators so much as just taking charge and eating regardless.

Tyrannosaurus vs. Quetzalcoatlus

Shortly after T. rex opens up the body of the dead A. sanjuanensis and begins feeding, a large Quetzalcoatlus northropi lands and challenges the theropod to the carcass. This later turns into a two on one battle when a second Q. northropi arrives. Attenborough informs the audience that Q. northropi is one of the few creatures that would challenge an adult T. rex. Ultimately, the T. rex decides that this meal isn’t worth the fight and walks off, leaving the two Q. northropi to gorge on the corpse.

So, this scene garnered a lot of talk online. Twitter was rife with people arguing for or (mostly) against this type of interaction. This online talk did make its way to Naish, who covers his thinking of it in the Megathread. As for me, I do have problems with this scene, but I’m less bothered by the thought that a large azdharchid could bully a T. rex. I think that T. rex suffers from a cult of personality problem in which many people view it as the top predator rather than just a normal animal. Naish rightly brings up cases in which large predators can be scared off by much smaller mesopredators and even prey. It’s not unheard of for a predator to have an “off day” and feel like a fight is not worth it, or to get “short circuited” by a smaller animal acting much tougher than expected (ever run from a spider or ornery chicken?).

No, my problem with this scene and the reason why it gets a sin is because the carcass that is being fought over is humongous. In the opening of this scene Attenborough states that A. sanjuanensis weighed 80 tonnes. If that T. rex was the size of the most liberal estimates for FMNH PR 2081 (13 tonnes, Hutchinson et al. 2011), that dead A. sanjuanensis would be over six times larger. That’s a lot of meat (literally tonnes). A feast that size is worth fighting for. However, at such a massive size discrepancy, it’s also a feast that doesn’t require any fighting. A more realistic portrayal here would have been T. rex eating the dead A. sanjuanensis while ignoring the two azdharchids and troodontids that are also eating nearby. It would be similar to reports of Great White sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) and tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) sharing a meal of dead whale together. As long as enough food is around, predators don’t feel the need to be all that territorial (see also: Scott et al. 2025).

So, one sin for this and one sin for the statement that Q. northropi was one of the few animals that would challenge a T. rex. We have no idea about that. This is where the show’s underlying pterosaur bias goes too far.

Mostly speculation

A behemoth among behemoths

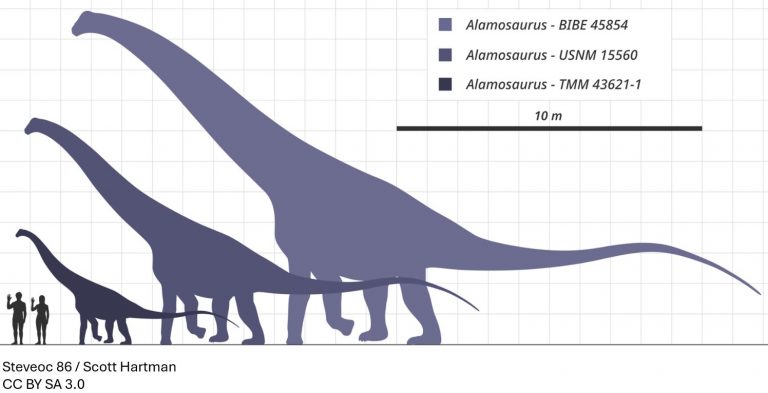

When the audience is first introduced to A. sanjuanensis Attenborough states that each animal was 30 meters (100 ft) and weighed 80 tonnes. That is not only huge, but up there with the upper echelons of the largest sauropods ever. In the Megathread Naish states that we have found specimens that are estimated to be that large and cites this image from Dr. Scott Hartman.

The largest specimen in this image is Big Bend (BIBE) 4584, which was reconstructed at 26 meters (85 ft) in length based on a composite skeleton for the Perot Museum (Tykoski and Fiorillo 2017). So, the population shown in Prehistoric Planet is still upsized from reality by a few meters. Whether it hit 80 tonnes is harder to say as there are no solid mass estimates for this genus. However, the equally (?) large titanosaur, Argentinosaurus huinculensis has been estimated to be around 56–119 tonnes, and the slightly smaller Dreadnoughtus schrani at 36–74 tonnes (Campione and Evans 2020). So, 80 tonnes is a believable mass for the largest individuals even if we can’t really be sure here.

I would also direct people to Hartman’s blog regarding skeletal reconstruction of A. sanjuanensis and the challenges associated with it.

How old is old?

In this scene an old A. sanjuanensis dies overnight and becomes the site of all the interaction later on. Attenborough informs the audience that this A. sanjuanensis was 70 years old and at the tail end of its life. We don’t know how old dinosaurs could get, but preliminary growth curve data for some large sauropods suggests that an animal like Apatosaurus ajax, could take 70 years just to reach somatic maturity (Lehman and Woodward 2008). Couple that with broader surveys of dinosaur skeletons indicating that most dinosaurs never reached somatic maturity (Hone et al. 2016), and a 70-year old individual suddenly doesn’t seem that old. This doesn’t mean that adult sauropods were regularly centennial or even bicentennial animals, but it does suggest that some animals would be capable of reaching these ages. The 70-year cutoff almost feels like a mammalian choice. Most large mammals don’t live much beyond 70 years. Exactly why is a topic of debate, but one hypothesis is that loss of teeth at that advanced age makes it impossible to keep eating effectively (e.g., Johnson et al. 1965). This would not be an issue for sauropods as they likely had reduced or no senescence, similar to data from other reptiles (Paré and Lentini 2010; Slowiak et al. 2021).

In short, 70 may have been old, or it may have been “middle aged”.

Dangerous lance

During the T. rex Q. northropi standoff Attenborough informs the audience that one strike from the 2 meter long beak could cost T. rex an eye. While that is a potential real threat, that would also have to be a very lucky strike. T .rex eyes are not all that big compared to its skull (10% of skull length, Lautenschlager et al. 2023). A Q. northropi stab would more likely hit the greater part of the face, which would still hurt, but wouldn’t be life altering like an eye stab. So, while I agree with the potential danger of the beak, I think that the greater danger would always be from the jaws of T. rex should it latch onto any part of that azdharchid’s body.

I’m giving this one a sin for the unlikelihood of that attack landing and the omission of the T. rex side of that fight.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Overall reconstruction of Alamosaurus

Known as the largest and possibly only sauropod species of Late Cretaceous North America, A. sanjuanensis is known from multiple specimens, yet few of them provide good material (see Tykoski and Fiorillo 2017 for a bit of a review). Naish covers this in the Megathread and mentions how interpretations of body proportions and osteoderms relied heavily on other, better-preserved titanosaurs. Due to that I’m giving a minor sin for the current reconstruction being a chimaera of other titanosaurs. This also covers movement and neck placement.

Annoying artistic choice

Inflatable noses return

The Alamosaurus sanjuanaensis individual that dies is shown breathing heavily through its nose, causing the nasal capsule to pulse in and out. This is not how these nasal cartilages are built. Even heavy breathing won’t show up as much from an external perspective.

Scene 2: Gulf of Mexico

Baseless speculation

Ammonite reproductive history

One of the star animals in this scene are large ammonites from the genus, Sphenodiscus. Attenborough informs the audience that females are traveling up from the depths to lay their eggs in the shallows. We have no evidence to support this behaviour for Sphenodiscus or any other ammonite.

Surplus killing by Globidens

The other star animal in this scene is the mosasaur, Globidens dakotensis . Upon catching up to the Sphenodiscus shoal, G. dakotensis starts biting on several individuals, causing them to sink to the bottom of the sea bed where G. dakotensis later returns to eat them. The mosasaur kills several more than it would have eaten. This type of surplus killing is mostly seen in a few mammals today (e.g., Kruuk 1972), with rarer observations for some birds (e.g., Solheim 1984) and Naish states in the Megathread that this is also seen in some insects. Surplus killing is rare today and requires unique circumstances (Oksanen et al. 1985). Not really something that should be highlighted in a show about “normal” life in the Maastrichtian.

Pulling out the soft bodies of Sphenodiscus

After “hamstringing” several Sphenodiscus individuals, G. dakotensis returns to its spoils where it pulls out the soft bodies of each prey and swallows them whole. This seems a weird method for devouring prey that were probably firmly welded into their shells. Why wouldn’t G. dakotensis just work on cracking through the shells and devour the animal that way? A similar method can be seen today in extant caiman lizards (Dracaena sp.), which would seem to be the most useful animals for an analogous comparison to an extinct squamate with durophagous dentition. According to the Megathread, Naish seems less confident in ascribing durophagous diets to reptiles with durophagous dentitions, which seems a strange logic. See the Dracaena example below.

Similarly, I don’t see how one can “do their homework” for reconstructing what the soft parts of an excised ammonite would look like given that we have no such soft parts to work with.

Mostly speculation

Jetting Sphenodiscus

As discussed in the Megathread, some species of Sphenodiscus had shell lengths up to 40 cm (16 inches). These would have been solid prey animals for G. dakotensis. As the audience watches a shoal of Sphenodiscus move through the water, Attenborough informs the audience that a combination of their streamlined profile and a powerful siphon enables them to shoot through the water at great speed. So far as I can tell, there is no evidence for a jetting siphon in Sphenodiscus. There is a siphonal band that has been proposed to house a siphuncle, but interpretations of this have been controversial and of little use for jetting (Kennedy and Cobban 1976). More interestingly is the discovery of aptychi (bivalved plates found in pairs within the body chambers of many ammonites, Parent et al. 2014). The exact function of this structure in ammonites is still up for debate, but at least one hypothesis included jetting (Westerman 1990). This is the closest I have come to finding anything like a jet siphon in the fossil record of ammonites.

As discussed in the Megathread, jetting was inferred for these species based on how other cephalopods move about. It’s worth noting that extant Nautilus do utilize this type of jet propulsion, though it doesn’t move them all that fast (max of ~25 cm/s, Parent et al. 2014) compared to the speeds seen in cuttlefish, squid, and octopodes (e.g., 10 m/s, Vogel 1987). Ammonites were certainly a diverse enough group that jetting likely was present in some of these species, but specific groups are harder to nail down. Hence the sin.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Out of place Globidens

The main vertebrate star in this scene is Globidens dakotensis. At least, that seems to be the case. As is typical for Prehistoric Planet, the species name is not given, but the Twitter Megathread does say that G. dakotensis was used as the template for this species. As the name implies, G. dakotensis is found in the Dakotas (South Dakota) and not around the Gulf of Mexico. It’s also from the Middle Campanian, making it too old for this location (Driscoll et al. 2019). A seemingly better candidate would have been G. phosphaticus, as it’s known from the Maastrichtian. However, G. phosphaticus comes from Angola, Africa (Driscoll et al. 2019), making it a worse fit. There is a potential Globidens species from the right time and place (Buchy et al. 2007), but its affinities don’t fully align with Globidens, so it remains undetermined for now. Technically, the Globidens shown in Prehistoric Planet, doesn’t really line up with any specific species. However, since G. dakotensis is known from better material, and was used as the “template” for the episode’s Globidens, I would say that this is the most likely species or species look-alike shown in the episode, which may not be accurate for the time and place shown.

Egg sac attachments

Near the end of the scene the surviving female Sphenodiscus attach a single egg sac (with thousands of eggs in it) to rocky crags around the ocean floor and abandon them after that. As with the Oceans episode, we do have some primary evidence for the size and shape of an ammonite egg sac (Etches et al. 2009). We can also infer some life history traits for ammonites based on extant cephalopods that all basically show the same “lay’em and leave’em” approach (adults typically die a few days later).

Nonetheless, the specifics for egg sac location, number, and attachment cannot be fully supported by the fossil record, nor can the extant phylogenetic bracket style inferences.

Incapacitate rather than devour

In the scene, we see G. dakotensis swim through the Sphenodiscus shoal and bite several individuals, cracking their shells and thus causing them to lose their positive buoyancy and sink to the ocean floor where G. dakotensis later stops by to scoop them up. We do have some evidence for this behaviour in the form of tooth marks on ammonite shells that have been attributed to mosasaurs (e.g, Kauffman 1990). However, as noted in the Megathread, this interpretation is not without controversy in the literature. Some authors argue for limpet rasping after death rather than mosasaur attacks (Kase et al. 1998), while others have argued that the limpet interpretation is incorrect (Wahl 2008). So, it’s a bit of a mixed bag here on interpreting the data.

Regardless, the bite and release hypothesis is unique to Prehistoric Planet. It’s possible that this happened, but it’s equally possible that the smaller ammonites were swallowed whole while the larger ones were cracked a few times in the mosasaur’s jaws (see Dracaena example above).

Myth promotion

“Just” marine lizards

When the scene first opens and the audience sees G. dakotensis swim by, Attenborough informs the audience that these reptiles “may look like huge sharks, but they are in fact a kind of aquatic lizard.” Couple this with Dr. Habib’s statement in the Oceans Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment referring to mosasaurs as a “whale-sized Komodo dragon” and the myth that mosasaurs were just “marine lizards” continues. I’ve been meaning to do a deep dive on mosasaurs for a while. Maybe that will happen next year, but for now I’ll say that the idea that these marine reptiles were “just lizards” does immense disservice to just how much this group had changed from a “typical” terrestrial lizard. It’s as misleading as calling whales “just aquatic cows”.

Bad artistic choice

“Tiger” ammonites

We see a return of ammonites in this scene. This time we see species in the genus, Sphenodiscus. Attenborough refers to these ammonites as tiger ammonites, based on their tiger striping. According to the Megathread, this was an invented name for an idea that the production team had for what these ammonites would have looked like in life. In other words, they made up a look and then gave it an even more made up “common name”

Three sins for that.

Scene 3: Lake-side in Wyoming

Baseless speculation

Flocking Styginetta

The first animal to appear in this scene is the bird species, Styginetta lofgreni. This potential presbyornithid is shown living in flocks around a soda lake. To date, the only material we have for S. lofgreni are six scapulae, a carpometacarpus and part of the sternum (Stidham 2001). That’s not really enough to accurately reconstruct the animal (or possibly even name. More on that below), much less assume some type of flocking behaviour.

Pectinodon bakkeri…just all of it

The other main character in this scene is the troodontid, Pectinodon bakkeri. The animal is portrayed as a fully-fleshed out (and feathered) animal despite being known only from a single tooth (Carpenter 1982). Now, according to the Twitter Megathread, Naish and the PP team didn’t use the original description to reconstruct this animal, but instead relied on an unpublished specimen that has better material. We’ll revisit this again later. For now, regardless of the material chosen, there is not enough data to accurate reconstruct what P. bakkeri looked like.

Brine flies for dinner

In this scene we are shown young P. bakkeri eating several brine flies from a swarm gathered over the soda lake. As far as I can tell, we have no evidence for the existence of brine flies (ephydrids) in the Cretaceous. Most discussions of ephydrid fossils (or traces) occur in the Cenozoic (e.g., Esther et al. 2013). The presence of brine would be a normal event in the Cretaceous (or as normal as it is now), so there’s a good chance that animals like brine flies (if not true brine flies) could be present at the time. However, neither a soda lake nor brine flies are based on any primary data and should be considered completely made up for the sake of the show. I’ll also note that Naish was aware of this during production, and discusses this a bit in the Megathread.

The intelligence of Pectinodon

As the audience is shown the juvenile P. bakkeri flail about trying to eat as many brine flies as possible, Attenborough informs the audience that Pectinodon are particularly intelligent dinosaurs. Given what I already mentioned above regarding the preserved material for P. bakkeri , this is completely made up. The only thing that PP can really lean on here is that P. bakkeri is considered to be a troodontid, and Stenonychosaurus inequalis (i.e., the real Troodon) has been shown to have a particularly high encephalization quotient (Jerrison 2004), leading to speculations on the intelligence of troodontids as a group. Whether such EQ values can really be extended to all troodontids, their validity, and whether they can really be associated with the nebulous phrase, intelligence, is up for debate. Regardless, we have none of the necessary data for P. bakkeri.

A similar problem is evident in the follow-up phrase from Attenborough stating that P. bakkeri were skillful hunters.

Two sins here. Both for assigning a bunch of high-level traits to a fragmentary taxon.

Parental feeding…again

After P. bakkeri successfully kills an S. lofgreni, the father brings his catch to his brood, allowing them to feed off it. This reconstruction approaches mammalian-levels of parental feeding here (think big cats). Most birds don’t even extend their feeding to this extent. It was doubtful that any dinosaur was doing this, much less the majority of them as shown in Prehistoric Planet.

Mostly speculation

Return of the paternal parent

As with Ice Worlds and Badlands, Prehistoric Planet opts to show P. bakkeri as a doting single father. In the Megathread, Naish discusses how this is based on a previous study showing that paternal only care may be the ancestral state for pennaraptorans (Varricchio et al. 2008). I’ve highlighted the problems with this paper in a previous installment. Those same problems still apply here. All the more so given what little we know about P. bakkeri.

Misinformation

The rise of the Rocky Mountains

As this scene first opens up, the audience is treated to B-Roll of a soda lake as Attenborough informs us that powerful movements beneath the Earth’s crust are beginning to raise the Rocky Mountains. However, the Rocky Mountains were already well underway by the Maastrichtian, with their estimated start being around 80 million years ago, during the Campanian age (English et al. 2004). Attenborough should have said something more along the lines of: these tectonic movements have continued to thrust the Rocky Mountains into the sky, dividing North America.

Ethical worries

Choice of taxa

This should probably the most controversial episode of Prehistoric Planet, as the two star taxa in this scene are both pulled from questionable sources. S. lofgreni comes from an unpublished dissertation by Dr. Thomas Stidham (2001). The lack of publication on this specimen could indicate that the relatively scarce material used to assign a species to it was not enough to warrant a new taxon. It’s also possible that Dr. Stidham has been too busy to revisit the material. Regardless, it remains an officially undescribed species (hence the lack of italics) that Prehistoric Planet sought to thrust into the spotlight. Naish discusses this a bit in the Megathread. Despite the argument for choosing S. lofgreni, the fact that it is an unpublished specimen makes the choice sketchy and ethically questionable. Ironically, the PP team would have been better off just choosing a species of Presbyornis and just sticking it in the wrong time, much like they had been doing with Velociraptor mongoliensis, or Globidens dakotensis etc.

The other unsavoury note comes from P. bakkeri, a species that was named based on a single tooth (Carpenter 1982). As discussed in the Megathread, Naish and the PP team opted to go with an unpublished, private specimen that is alleged to be much more complete. There has been a lot of hay written about the utility and morality of using private specimens. While I prefer a more nuanced approach to the all or none view taken by many in these arguments, I think relying on a private specimen to reconstruct a prehistoric animal for public consumption is equivalent to just making things up entirely.

Three sins for questionable paleontological ethics.

Missed opportunity

More broken arms

When P. bakkeri attacks the flock of S. lofgreni, it does so by leaping into the air and snapping at the birds as they fly away. At no point in the entire sequence does P. bakkeri use its arms. Not to help snatch at prey, nor to help it get airborne (if it has wings, why not flap them?). Once again, Prehistoric Planet treats theropod arms as broken vestiges.

Scene 4: Rocky Mountains

Continuity error

This next scene takes place further north than in Scene 3. Here, Attenborough correctly informs the audience that the Rocky Mountains are continuing to rise at this point in prehistory, directly contradicting what he mentioned just six minutes earlier.

Baseless speculation

Rutting Triceratops

As with Forests and Swamps, Triceratops is portrayed as a herd-living animal despite a near complete lack of data for this. This time the audience is shown a herd of Triceratops horridus gathering for a mating rut in which males compete for females using head-to-head sparring matches. According to the Megathread, these are individuals that have gathered together for mating rights, but the presence of females with calves and a lack of narration to the contrary suggests that this is more like several herds coming together.

Regardless, the sin here isn’t for (once more) showing T. horridus as a herd-living animal, but rather for this idea of an annual rutting season. This is a very mammal-centric view of dinosaur courtship that has no basis in the fossil record, nor much support from the extant phylogenetic bracket.

Females choose a mate from the males

Attenborough informs the audience that the females have come to choose a mate, which seems a little off if the thrust of the scene is to show males fighting each other for access to females. Regardless, we have no evidence that any of this happened.

30-year “old” Triceratops (no sin)

The big male in this scene is said to be a 10 tonne, 30-year-old individual. According to the Megathread, it was based on Museum of the Rockies (MOR) 3027 (Yoshi), and “aged up” to 30. No real issue here, save a statement from Naish in the Megathread that alludes to the old idea that dinosaurs “lived fast and died young”. This now outdated concept of dinosaur life history was brought about by misreading the osteohistology (see Chapelle et al. 2025 for a good summary). Naish also relies on unpublished data on Triceratops osteohistology to base this hypothesis of “old” for the PP T. horridus, which has a similar whiff of iffy ethics here. Since none of this is mentioned in the show, I’m not going to give a sin here, just a side note.

Dueling Triceratops charge into one another

The large male and the young upstart charge into one another before locking horns. This would seem to be a very dumb maneuver for a large, horned animal to make. The “goal” of the joust isn’t to kill the rival but rather to showcase one’s strength via “head wrestling”. By running at each other first, the risk of a fatal injury (not to mention concussions) skyrockets. When looking at extant horned animals, combatants line up first and then shove their horns at each other (see: Carpenter and Ferguson 1977; Caro et al. 2003). Big horn sheep and musk ox will ram into one another, but their horns curve away from their attackers, giving everyone a better “fighting chance” (Lundrigan 1996). While the entire rutting and fighting scene is based on nothing, the idea of having two large animals rush at each other with biological spears seems like a catastrophically poor decision.

Mostly speculation

Triceratops mating posture

Shortly after the big male wins his bout, he proceeds to mount a receptive female for procreation. The method by which this occurs is mostly speculative, though I will say that there has been one attempt at figuring it out (Isles 2009). The author performed a comparative study utilizing extant analogues and some extant phylogenetic bracketing to come up with some workable poses. The study was mostly inferential, and I disagree with the author tossing lepidosaurs out because their tails were too bendy (dinosaur tail stiffness has been vastly overexaggerated), but I applaud someone at least trying to figure this problem out.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Triceratops combat

The main part of this scene is the shoving match between the smaller T. horridus and the larger male. The method chosen for this test of strength was to have the two animals lock horns together and perform a shoving match. As discussed in the Megathread, there is a fair bit of study that has gone into this. The idea of a shoving match between ceratopsians was first hypothesized by Dr. Andrew Farke (2004) and others (Farke et al. 2009) based on scale models and comparisons to similar-shaped animals such as the lizards in Trioceros, and some cervids. Importantly, Farke et al. (2009) identified osteological correlates of horn scrapes and punctures that support this style of fighting. I disagree with Naish’s description in the Megathread that individual Triceratops would have the goal of stabbing the other based on preserved damage on the bones and comparisons with extant horned taxa such as Trioceros. That is not what the data from Farke et al. 2009, nor the initial description from Farke 2004 support. I suspect this may be a misinterpretation of the data, in part due to the side mention that these chameleons may also engage in stabbing along with shoving (Farke 2004). This was based on information from Carpenter and Ferguson (1977). However, the original paper never mentions stabbing attempts in horned species. Overall, this part was fairly well supported, even if all the extra rules were all speculative.

Scene 5: Alaska

Baseless speculation

The “Cold far north of the Americas”

This scene opens up on a B-Roll shot of modern-day Alaska (possibly) showing a snow covered landscape across a massive mountain range. Attenborough informs the audience that this cold far north make food harder to find during some parts of the year. As with Ice Worlds and Islands, this is a seemingly active misinterpretation of the data for Alaska and the paleo poles. As stated several times in those Megathreads, the Prehistoric Planet team leaned heavily on a commissioned (but never published) paleoclimate model to determine the climate at the poles. I went into detail on my misgivings of this model in the Ice Worlds episode. Those same misgivings apply here.

The sun rarely rises here

As the B-roll continues, Attenborough states that at the Arctic Circle the sun barely rises for three months out of the year. In this scene, the audience is shown a mostly clear sky. However, as noted in the Ice Worlds episode, Farnsworth and Spicer’s own climate model indicates near continuous cloud cover (the Pacific Northern Gyre) throughout the year. This is internally inconsistent with the data that Prehistoric Planet commissioned.

The look of Nanuq…saurus

As discussed in Ice Worlds (where we first saw N. hoglundi), the presence of heavy (or any) filamentous covering in a tyrannosaurid is bordering on anti-scientific given the work done by Dr. Phil Bell and others. Same sin as in that previous episode.

Ornithomimus out of place

This scene takes place in the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska, where it features the tyrannosaurid, Nanuqsaurus hoglundi and the eponymous ornithomimid, Ornithomimus edmonticus. As admitted to in the Megathread, O. edmonticus is not known from the Prince Creek. There are some indeterminate ornithomimid fossils from the Prince Creek, but they cannot be solidly associated with Ornithomimus, nor even ornithomimidae (Fiorillo 2018). Nonetheless, the presence of a potential ornithomimid was enough to justify adding one to this scene. That said, it still should not have been O. edmonticus. Naish states that the “Velociraptor” rule fell in place here, despite readily violating said “rule” in previous episodes. Sin for the misinformation.

Wrong environment

Both dinosaurs are shown in an open, grassland environment rather than the coastal floodplain of the Prince Creek (Fiorillo 2010). Naish mentions this shortcoming in the Megathread and points to production limitations and the 2020 pandemic as reasons why the shooting location didn’t fit. While this was an unfortunate and somewhat unavoidable series of events, the sin still stands as this was meant to be viewed as a documentary.

Pursuit hunting

The big event in this scene involves N. hoglundi attacking the herd of O. edmonticus across the grasslands in a prolonged chase sequence. The sequences only lasts for a minute at a time, which is well within the typical range of short-term pursuit hunters like varanids and big cats, but given that the environment that N. hoglundi comes from would have been more heavily forested, it would seem more likely that an ambush-style hunt would have taken place (more akin to Qianzhousaurus sinensis from the Forests episode). I’m giving this one a sin for giving a different hunting style to a taxon so as to match the environment that was filmed rather than the environment that the animal would have lived in.

Also, because N. hoglundi roars to scare the herd into running, which is not a thing predators do. It also “roars in frustration” upon losing the chase the first time, which is a very anthropomorphic response.

Spring winds bring sharp temperature swings

After losing the first chase, the camera pans out and moves to a B-roll of timelapse cloud movements. During this scene Attenborough states that “It may be spring, but this far north, freezing winds can quickly cause temperatures to fall”. Once again, the only evidence for “freezing winds” seems to come (secondarily) from the weather model by Farnsworth and Spicer. Given the near omnipresent Pacific Northern Gyre hypothesized to be in the Arctic (Herman and Spicer 1996), such massive temperature drops seem unlikely.

Nanuqsaurus uses the snowfall to better sneak closer

The presence of a sudden (light) snowfall help mask N. hoglundi‘s approach somehow. The filamentous coat given to N. hoglundi is brown rather than white, so the theropod just sticks out even more with the newly fallen snow. In contrast, the white plumage given to O. edmonticus is a better camouflauge for this environment. So, the concept here doesn’t really make sense. Also, the presence of more snow in an area that would have rarely seen snowfall. Same sin as in Ice Worlds.

More parental feeding

After a successful kill, the female N. hoglundi returns to her brood with her spoils and lets them eat what she caught. Once more, a behaviour that is believed to have evolved deep within Aves (Neoaves, Starck and Ricklefs 1998) and some predatory mammals, is shown as commonplace among dinosaurs. Changing the parent to a female instead of a male this time doesn’t change the lack of data.

In short: no evidence for this.

Mostly speculation

Plumage in Ornithomimus

As this is the same animal from Ice Worlds, it’s the same sin mentioned there.

Speedy Ornithomimus

As the scene first starts and the audience is reintroduced to O. edmonticus, Attenborough informs them that these “fleet-footed travelers are among the fastest runners of all dinosaurs”.

Based on body proportions, ornithomimids appear to have been built for a speedy getaway. Whether they were topping the charts for fastest dinosaur is harder to say, especially in light of more recent data suggesting that we have been overestimating dinosaur speeds (Prescott et al. 2025).

Nanuqsaurus was faster and more agile than Tyrannosaurus

This is largely (pun unintended) based on the smaller size of N. hoglundi compared to Tyrannosaurus rex. Biomechanical modeling does show a drop in estimated maximum speed and acceleration in theropods as they got bigger, with smaller theropods having the edge here (Hutchinson 2004). That said, we know very little about the size and shape of N. hoglundi (no limb material are known), so there is a still a hefty bit of speculation thrown in here.

Final sin count: 51