For a primer on this blog series and an FAQ see here.

| Other Episodes |

||||

| Coasts | Deserts | Freshwater | Ice Worlds | Forests |

| Islands | Badlands | Swamps | Oceans | North America |

This episode features contributions from the following paleontology consultants:

- Steve Brusatte

- John Conway

- Alexander Farnsworth

- Kiersten Formoso

- Michael Habib

- Scott Hartman

- John Hutchinson

- Christian Klug

- Takuya Konishi

- Neil Landman

- Luke Muscutt

- David Peterman

- Peter Skelton

- Robert Spicer

- Paul Valdes

- Mark Witton

- James Witts

- Darren Naish

This episode has the most input from paleontologists, likely due to it covering such a vast, diverse, and really hard to undrestand area of the prehistoric world. As discussed in the Twitter Megathread for this episode, Oceans is largely a continuation of the first episode, Coasts.

Scene 1: Oceans off Western Europe…and Japan?

The species shown in this scene are Mosasaurus hoffmani and Phosphorosaurus ponpetelegans As is typical for Prehistoric Planet, the species names are never mentioned (M. hoffmani gets mentioned in the Prehistoric Planet: Uncovered segment for this episode), which makes it harder to nail down specifics. The Twitter Megathread specifically talks about these genera coming from Western Europe and Japan. The problem is that even with adjustments to continent placement for the Maastrichtian, that range is too massive to make any sense for a singular scene in this show. Both genera of mosasaur have representatives in each location (M. hoffmani and P. ortliebi from Europe. M. hobetsuensis and P. ponpetelegans from Japan) which adds to the confusion. Given that M. hoffmani is specifically mentioned in the Prehistoric Planet: Uncovered segment for this episode, that should mean that our hallisaurine is P. ortliebi. However, P. ponpetelegans is known from better material…and this scene specifically references pieces from the original descriptive paper (Konishi et al. 2016). Further, the breach scene (Scene 4) happens in the South Pacific, where P. ponpetelegans is more closely located. As such, I’m going to say that this is taking place in Japan and that the Prehistoric Planet team is moving M. hoffmani past its known range. This mess would have been so much easier to work out if the show had mentioned where this was taking place. Paleontologists could also treat species epithets with more respect, but that’s a sin for another time.

Baseless speculation

Breath-hold time for Phosphorosaurus

The audience is introduced to a small representative of Phosphorosaurus ponpetelegans . Naish mentions that they opted for a deliberately smaller individual than found in the fossils so as to showcase the individual variation that would be expected within a species. That’s all fine and good but doesn’t really mean anything when it is shown in a vacuum like this. Regardless, that’s not the sin here.

The sin comes when Attenborough states that this young female has to come up for air once or twice an hour, thus inferring a typical breath hold time of 30–60 minutes. As a secondarily marine animal we should expect some long breath hold times. However, the specific caps on dive time here is beyond our measuring capability. The dive time given by Attenborough is within the range of maximum values recorded for sea snakes (Heatwole 1978) and sea turtles (Okuyama et al. 2012), but greater than the maximum dive times of many seals (Hindell et al. 2000; Sparling et al. 2007) and cetaceans (Noren et al. 2000). There is a lot of slop in the data for marine animal dive times, and they all come from extant animals that we can actually measure. For an extinct animal known only from fossils, we haven’t a clue what an average or a maximum breath hold would be.

Nocturnal hunter

To avoid being preyed upon by larger mosasaurs in the region, P. ponpetelegans spends her day within the rocks of the reef and only ventures out to forage at night. This is a cool story but it is one without any data to support it. P. ponpetelegans may have been a nocturnal hunter based on the large orbit of this genus. Naish further argues that the presence of lantern fish (Myctophidae) fossils in the same area could indicate that P. ponpetelegans preyed on these animals.This hypothesis comes from Konishi et al. (2016) in their original description of P. ponpetelegans. I think it’s a pretty big maybe as we only have association here and not gut contents. Without scleral rings to estimate orbit shape we really can’t say one way or another on the activity times of this species. To Naish’s credit in the Megathread, he does urge some caution with some of the paleobiological interpretations (in this case, surrounding binocular vision).

.

Mostly speculation

Staying close to the reef for protection

The P. ponpetelegans female in this scene is shown staying close to the reef to avoid predation from larger predators patrolling the area. This has precedence in how many extant animal avoid getting predating upon in reef settings, but we have no way of knowing if this was happening back then for this species.

Lantern fish migration from the depths

As discussed above, we do have evidence that myctophids were present in rocks from this formation (Uyeno and Matsui 1993). The fossils preserved include near complete skeletons with soft-tissue outlines. So, the reconstructions should be pretty cleanly done…assuming the animators didn’t lean too much on extant myctophids as a crutch…which they kinda did.

So, that’s a bit of a disappointment, but it is understandable given the budget limitations coupled with the overall difficulty of animating ocean-living things. As for the vertical migration, we have no idea, but some extant myctophids do showcase this behaviour (e.g., Dypvik et al. 2012) so it is plausible to think that a version of this was happening in the Mesozoic as well.

Missed opportunity

Phosphorosaurus relies on vision over vomerolfaction to snatch her prey

Prior to the bait ball scene (also speculative but so many different extant species do it that I’m okay with letting it slide) we see P. ponpetelegans sampling the water with her tongue in a manner similar to extant autarchoglossans. This was cool to see and it has a fair bit of data to back it (e.g., Schulp et al. 2005). It would have been nice to see P. ponpetelegans (or any mosasaur) use that keen sense of vomerolfaction to root out their prey as opposed to just using vision.

Scene 2: The Western Interior Seaway

This scene is interesting in part because the Western Interior Seaway may not even have existed by the Late Maastrichtian (Berry 2017 offers a nice summary of the debate). As there are current models that keep the seaway open through the K/Pg, the interpretation in Prehistoric Planet is justifiable.

Baseless speculation

Late-surviving Hesperornis

The star of this scene is the eponymous hesperornithid, Hesperornis regalis. The problem that immediately crops up here is that H. regalis appears to have gone extinct by the Late Campanian. So, this species is out of place by several millions of years. The closest potential species would be a partial tarsometatarsus described by Hills et al. (1999) that may date to the Early Maastrichtian, but even that was considered unlikely. This timeline is a problem that Naish addresses in the Megathread and argues for a more hopeful “some species may have persisted” approach. This is a problem with limiting a show like this to a single time period. What’s even the point if one is going to make exceptions here and there just to get a favourite species on screen?

Mostly speculation

Speedy Xiphactinus

The other star of this scene is the ichthyodectid, Xiphactinus audax. This species is a popular one to depict in paleo-art due to the sheer size and generally “monstrous” appearance. As to whether they are one of the fastest fish in the ocean at this time is another matter entirely. We have a lot of good data for the size and shape of X. audax but no data on their swimming style nor swimming speed. So, this part seems to be made up.

Bad artistic choice

X-Fish

When we are first introduced to X. audax Attenborough informs the audience that this species is commonly known as X-Fish. It is not. This is not a thing that has happened before and I hope it is not a thing that will ever catch on. This was Prehistoric Planet coming up with a kitschy common name for a fish with a name that could be considered hard to spell. It is talking down to the audience and expecting less from them.

Three sins for that abomination.

Scene 3: Oceans of Europe

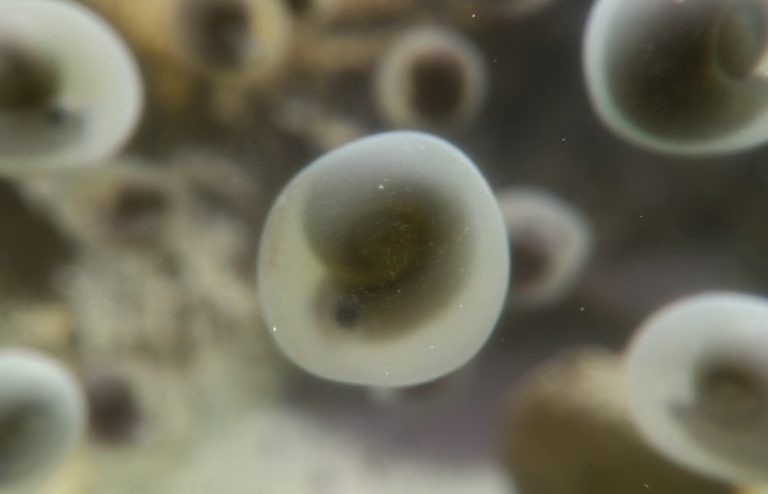

This scene focuses on ammonites. As discussed in the Twitter Megathread, there are thousands of ammonite taxa known throughout the Mesozoic. Prehistoric Planet appeared not to have really tried to nail down a specific species, genus, or even family for this scene, which is fine as this is made up for in Scene 5. That said, given the time period and location, these ammonites may best be considered members of the Pachydiscidae family. This group produced moderate to large-sized species, though none of that matters for this scene since it’s based only on hatchlings.

Baseless speculation

Ammonite nursery

This scene opens up on a tide pool where several thousand ammonite eggs have been washed in. Attenborough informs the audience that these tide pools offer refugia from the dangers of the rest of the sea, allowing these newly hatched ammonites a chance to develop in relative safety. It’s an interesting idea that some species may have taken advantage of. It’s also just as likely that this happened by accident. The data supporting or refuting it are nonexistent.

Ammonite babies work together to escape their drying pools

As the scene goes on the tide pools begin drying up, forcing the ammonite larvae to escape to wetter pastures. Attenborough informs the audience that baby ammonites can move together as a single unit, pushing their peers across dry rock to reach nearby pools. According to the Megathread this idea was inspired by what some larval crabs and tadpoles have been observed doing. While a neat phenomenon to see in real life, this doesn’t mean that we would expect to see anything like this in ammonites, despite their humongous variety and success throughout the Mesozoic.

Pyroraptor arrives to eat some hatchlings

To add an extra layer of danger to the moving mass of hatchling ammonites, Prehistoric Planet brings in Pyroraptor olympius. According to the Megathread, the idea was to bring in a dinosaur as a threat to the hatchlings (and likely to maintain perceived interest). The choice was the dromaeosaurid, Pyroraptor olympius. As I mentioned way back here, we have terrible fossil representation for this species. The sole reason it was chosen was because it fit the location and time period the best (Early Maastrichtian, though). Aside from that, there was no reason to bring this species in at all, much less make it into a cute scene wherein babies eat other babies.

That said, credit to PP for showing juvenile theropods hunting without parents around for once.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Hatchling ammonites

We are shown hatchling ammonites in all their over-the-top cute glory. Naish goes into details in the Megathread about how they did their best to avoid the cartoony cute factor, but still wound up in this borderline area. Exactly what a hatchling ammonite looks like is unknown. We do have some fossils of ammonite eggs (Etches et al. 2009), but these fossils only tell us about egg shape and offer a rough estimate for clutch size. Some embryonic remains (ammonitellae) are known too, but they only preserve the rough shape of the shells and not any soft tissue. The closest we can probably get to what a hatchling ammonite looks like is to compare it to a hatchling chambered nautilus (Nautilus; e.g, Shigeno et al. 2008).

I think Prehistoric Planet got close but likely bumped up the eyes to arms ratio too much.

Scene 4: Pacific Atoll

This scene features the return of the large Mosasaurus hoffmani from the first scene, along with the elasmosaurid, Tuarangisaurus keyesi. You may remember the latter species was also in the Coasts episode. In fact, this may be the exact same “pod” shown in that episode. This entire scene takes place in the South Pacific in a real geological structure called Darwin Rise. Much of this scene is inspired by South African Great White sharks (Carcharocles carcharodon) attacking seals.

Baseless speculation

Safety of the atoll

Attenborough informs the audience that this atoll acts as an oasis in the Maastrichtian sea, providing safety for the T. keyesi pod. There is no evidence for this or any habitat preference for T. keyesi.

Venturing to the depths for food

In an effort to set up some conflict, Attenborough informs the audience that T. keyesi must venture from the shallow atoll into the deep to find food along the canyon walls around the atoll. Once more behaviours are being placed on an extinct animal with no data backing it up. It’s just added for the sake of the story.

Ambush from below

Mosasasaurus hoffmani enters the scene as the major predator of the T. keyesi. M. hoffmani hunts its prey from the ocean floor looking up. This is where the scene’s Great White comparison becomes abundantly clear. Attenborough tells the audience that M. hoffmani is an ambush predator. Aside from overall size, we actually can’t be that certain if M. hoffmani or any Mosasaurus were ambush predators. Long bodies would suggest a more ambush tactic, but caudal fin shape suggests are more pursuit-focused ability (Lindgren et al. 2011). It’s likely that Mosasaurus was a fairly adaptable genus with varied hunting styles.

That said, attacking from below as shown is not based on any data. Hence the sin.

The breach

This is going to be a two-parter. The Twitter Megathread on this section takes its time and explains a few of the attempts that the team took to ground this scene in reality. Even the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment covers this section with interviews with Drs. Mike Habib and Kiersten Formoso on the mathematics that (kinda) support it.

So, why is it under baseless speculation?

Because the entire concept is made up. As discussed in the Megathread, it was inspired (copied) by great white sharks crashing into seals in South Africa. I bring up the specific region on purpose because this is the only place where great white’s have been recorded doing this. Even then, it wasn’t until this behaviour was briefly discussed in a BBC documentary from 1995/97 (depending on where one was) that anyone even bothered to look into it. Several years later, Discovery Channel’s Shark Week latched onto this behaviour as a great hook for viewership, birthing the concept of “Air Jaws”. The popularity of these scenes has not only likely encouraged, but also enhanced what was a rare behaviour in these sharks before. Thanks to modern media overemphasizing the rare, many have come to view great white breaching as a normal thing that they do. It wasn’t in 1997, and if Shark Week would stop sending film crews down their to purposefully entice the sharks it wouldn’t be a normal thing now.

So, that’s the stage. Breaching attacks are rare and largely useless (if you miss then you just blew a tonne of energy on nothing). Unfortunately, the breach idea has also taken a firm hold in modern-day paleo-art as can be seen in Figure 4 from Hone et al. 2018.

As discussed in Dr. Mark Witton’s blog post (in which he castigates the media for running away with something that his own art implicitly supports), this is a radical behaviour for a shark to take. Unfortunately, radical behaviours are not treated as such in paleo-art. Instead, rare and unusual events are treated as typical. It’s a side effect of the arts such as writing and movie making. One is encouraged to only write about the most interesting moments in a character’s life and to show the most dazzling view of that character. No one wants to see Peter Parker and Mary Jane making dinner and watching TV. They want to see Spider-Man swinging through the city. The justification for this in the arts makes sense when viewed through the lens of entertainment.

This approach makes for great art but it can be utterly toxic for science communication.

Mostly Speculation

Darwin Rise

As I mentioned above, Darwin Rise is a real geological structure (McNutt et al. 1990) representing a series of extinct underwater volcanos (guyots) that became the foundation of reefs, some of which breached the surface as atolls. There are some invertebrate fossils that support reef-building animals living in this region, but no vertebrate fossils correspond to this area (Matthews et al. 1974). So, there is no direct evidence that any marine reptile was utilizing this area for food or refuge.

That said, given that it was a reef system for most of the Mesozoic, it’s very likely that it was a regular place for marine reptiles. We just don’t have any primary evidence for it at this time.

Hunting style of Tuarangisaurus

Early in this scene we are shown a “pod” of T. keyesi hunting by swimming through shoals of fish and snapping them up as they go. This seems a weird choice for showcasing hunting strategies of elasmosaurs as it removes the need for the neck. It would have been more interesting to see some of the myriad other hypothesized hunting hypotheses for elasmosaurs (e.g., Massare 1988; McHenry et al. 2005; Zammit et al. 2007) as opposed to the “they acted like fish” behaviour that we are shown.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

The breach revisited

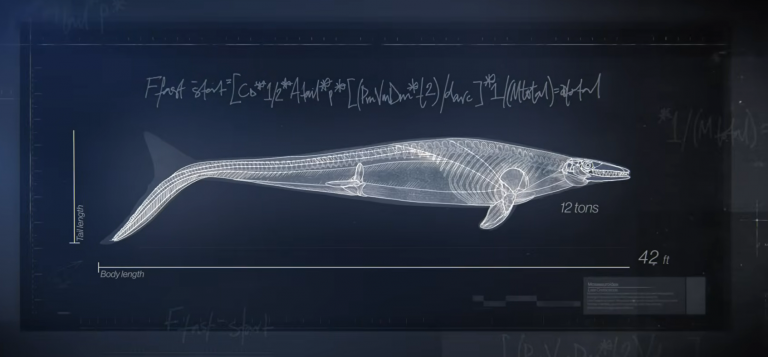

Onto part two of this scene. This time I’m focusing solely on the math behind this behaviour. In other words, could M. hoffmani actually pull this off?

According to the Megathread, it could not only pull it off, but it could do so with a several hundred kg animal in its jaws. As I mentioned, the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment delves into some of the grittier details of how this biomechanical event could be pulled off. This is a bit off focus as I’m looking at the Uncovered Segment itself as that is where all the semblance of science is hiding out. According to the calculations from Habib and Formoso (maybe. It’s just what PP shows they did. There is currently no publication), M. hoffmani was 12.8 meters (42 ft) long and 12 tonnes in mass, which is slightly smaller than 15.2 m (50 ft) statement that Prehistoric Planet made at the start of this episode. That may have been important for the final calculations.

To figure out the power needed to get M. hoffmani airborne requires figuring out the force needed to propel this mosasaur out of the water fast enough to keep drag and gravity from pulling it back down before it left the water. According to the Uncovered segment, this was partially done using this equation:

The script used for the equation above is hard to decipher but seems to be a fast start equation that is calculating the power needed to move an animal this size through a column of water at a given velocity. The fast start part will be important in a bit as that seems to be the big thing allowing the feat in the show to happen. According to Dr. Formoso, M. hoffmani would have been able to clear 3/4 of a body length in one second, giving it a velocity of 9.6 m/s (35 kph / 22 mph). The Megathread extends this estimate a bit to 48 kph (30 mph) which is closer to 87% of the body length of a 15.2 m M. hoffmani, so there is a fair bit of slop there.

As Dr. Habib mentions in the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment, that is a massive amount of acceleration. For comparison, a 1.6 tonne Ferrari SF90 Stradale has an equivalent acceleration (13.3 m/s2) and that’s a supercar driving through air. It’s really hard to believe that an animal 7.5x larger in a medium that is 800x denser is capable of achieving an equivalent acceleration. I just don’t buy it.

Habib, and Formoso mention in the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment that this immense power delivery was made possible by the reptilian musculature of mosasaurs. Naish goes a step further in the Megathread by stating that reptilian muscle is about twice as powerful as mammalian muscle. It almost seems out of character for me to push back against an actually positive reptilian stereotype, but I do wonder how true that statement is. I’ve seen it mentioned from time to time regarding reptilian musculature and it all seems to stem from a paper from John Ruben (1991) regarding Archaeopteryx lithographica. In that paper, Ruben states:

This is related to a previously unrecognized attribute of reptilian muscle physiology: During “burst-level” activity, major locomotory muscles of a number of active terrestrial squamate reptiles generate at least twice the power (watts kg-1muscle tissue) as that of birds and mammals…

This is followed by a compelling graph (Figure 4) showing a substantial “burst speed” difference between mammalian, avian, and reptilian muscles (in Watts/kg). Exactly how these calculations were made is less clear in the paper (many of the referenced sources show non-transformed data), and a response from John Speakman (1993) called Ruben out for improperly comparing power output measures taken from mammals and birds, vs. reptiles. This, in turn, received a response back from Ruben (1993) in which he showed his work on transforming the data…and maybe adjusted the criteria some (focusing solely on fast glycolytic and fast oxidative glycolytic fibres). It’s a fascinating back and forth among physiologists that I think may have been missed in paleontology (despite the focal species). In short, if reptilian muscle is more powerful than mammalian or avian muscle it may only be true for those fast twitch fibres (FG and less so, FOG), which is likely due to the lower mitochondrial density in these fibres (Else and Hulbert 1985). There are other potential factors at play here too, such as multiply innervated muscle fibres with various twitch potentials outside of Mammalia (Gleeson and Johnston 1987), but the bigger deal seems to be mitochondrial density as mitochondria will create the fuel for the muscles but won’t add to its contractile power (i.e., high mitochondrial density will produce bigger muscles without the increased power). So, it may be true but we need more work done on reptilian muscle physiology to be sure

Returning to PP’s speedy M. hoffmani, if we compare its 13.3 m/s2 acceleration to extant marine mammals, the results seem very out of proportion. For example, data loggers for sperm whales between 9–15 meters (30–50 ft) in body length showed average dive and ascent accelerations of 0.97 m/s2 (Lopez et al. 2022 supplement). Large animals have a lot of inertia to overcome and just cannot generate the power needed to “get out the gate” fast (see Webb and de Buffrenil 1990 for a review).

That said, given the above talk about muscle power, these slower accelerations may just be a mammal thing. The whales that were tagged were not actively hunting in the same way that a mosasaur would. What about shark data? The results here are better, but not much better. The largest shark in the world, whale sharks (Rhynchodon typus) has a recorded max acceleration of 2.1 m/s2 (Cade et al. 2020). Smaller, more active predatory sharks aren’t much better (Ryan et al. 2015; Waller et al. 2023). The most detailed acceleration data for a shark would be tracking data on Great White sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), which fits as this is the most relevant species here. In C. carcharias, recorded ascent acceleration (attacks) were between 3–4.6 m/s2 for the South African (seal hunting) population (Klimley et al. 2001). All of the animals I’ve talked about so far can certainly go fast and some even exceed the estimated max velocity of M. hoffmani in the show, but it’s going to take more than one second to get up to those maximum speeds.

That’s okay, though, because M. hoffmani “cheats” in the show. Remember the fast start mentioned earlier? That’s where M. hoffmani is given an edge. In the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment, Attenborough and Dr. Habib explain the concept of a C-start in fish. This method allows fish to reach their max velocity in nearly an instance (slivers of a second), with accelerations that are near ludicrous. For instance, Norther pike (Esox lucius) can accelerate from a C-Start at 245 m/s2 (Harper and Blake 1990), allowing it to reach its maximum velocity of 7.06 m/s in 0.03 seconds.

Of course, E. lucius is substantially smaller than M. hoffmani (Harper and Blake’s specimens averaged 38 cm in length, which is smaller than a typical E. lucius). C-starts are size dependent as they rely on muscle contraction time, which is all affected by mass (Webb 1976; Dominic and Blake 1997). The explosive accelerations recorded in some fish would just not be possible in M. hoffmani.

Ah, but watching the segment again reveals something. Habib mentions that mosasaurs could do something very similar. Similar does not mean the same. Mosasaurs were not doing C-starts as they wouldn’t get anything out of it. In the Megathread, Dr. Formoso mentions (secondhand) that M. hoffmani would not do a true C-start and when we look at the visuals from the show this is pretty clear. M. hoffmani does not push against the water column when it takes off. Instead, M. hoffmani goes to the ocean floor and pushes off the ground itself. This will be much more effective as the resistance to movement will be so much greater from a solid floor as opposed to a fluid medium. It’s the equivalent of kicking off the pool wall when swimming and it gives this individual the massive burst of acceleration needed to achieve the desired result. Whether a 12.8 meter M. hoffmani could actually pump its tail at 1.8 Hz remains questionable, though (determined by counting frames/oscillation at 24 frames per second). That’s a pretty fast oscillation for such a large animal.

Okay, so M. hoffmani cheats by “kicking off the backboard” to get up enough speed to launch 3/4 of its body out of the water while holding a juvenile T. keyesi likely weighing a few hundred kilograms. Is this really sin worthy? There appears to have been a genuine attempt to figure out if a large mosasaur could act like a South African C. carcharias.

And that is the main reason it gets the sin. This entire mathematical backing appears to have been done not to test the performance range of mosasaurs but rather to support a behaviour that the production team already decided on. This is reminiscent of older Discovery Channel documentaries where “talking head” paleontologists were brought on after all the animations were done (or were being finished) and had to justify whatever nonsense the production teams already made.

To put it another way: The mathematics show that this behaviour was possible, not that it was probable.

I applaud Drs. Habib and Formoso for mathematically modeling a method that could support this behaviour, but I don’t like the back-calculation that appears to have gone on.

Also, sin worthy because Habib and Formoso haven’t published anything on this commissioned test yet. 🙂

Scene 5: Grass beds off European coast

This is a cool scene as it is solely focused on ammonites and the myriad forms that they took on. Still, things are far from perfect.

Baseless speculation

Bacculites the bottom feeder

The first named specimen to appear in this scene is Bacculites anceps. Attenborough informs the audience that it feeds near the sea floor. We don’t have any evidence for this behaviour. In the Megathread, Naish discusses data to suggest that B. anceps and kin were vertical floaters in the water column, which is fine, but bottom feeding evidenced is harder to come by.

Any feeding information for ammonites is hard to come by.

Nostoceras prefers the deep

Similarly to the above sin, Attenborough informs the audience that adult Nostoceras sp. (maybe N. hyatti) prefer the deeper waters of the sea floor. This is completely unknown, and as discussed in the Megathread, there is a lot of back and forth in the literature on exactly how these weird species even fed. The PP team took a position on this for the show (planktonivore) which I don’t think they should have without adding the appropriate caveats.

Mostly speculation

High mortality rate of ammonites

This scene starts with the unnamed ammonite species from Scene 3 making their way through the open ocean. Attenborough informs the audience that of that mass of thousands of eggs, only one in a one hundred survived the several months at sea.

While we have some good rough estimates for how many eggs a typical (?) ammonite laid (e.g., Etches et al. 2009) and we can see a similar pattern of high mortality in extant cephalopods, we don’t have the data needed to offer a quantified ratio such as 1:100. All we can say is that it was most likely that the majority of the young perished before they reached adulthood.

Ammonite soft-tissue shapes

For species like Diplomoceras sp (maybe D. cylindraceum), B. anceps, and Nostoceras sp. the specifics on the soft-tissue shapes for the mantle and arms remain mostly speculative. In the Megathread, Naish mentions how ammonites likely had webbing connecting their arms, though I’m not sure where that interpretation is coming from aside from a heavy reliance on phylogenetic inference (e.g., Jacobs and Landman 1993). Hoffman et al. (2021) mention that heteromorph ammonites such as Notoceras have had arm webbing proposed for them but without any data to support it. Webbing would aid immensely with plankton filtering…but we don’t have direct evidence for that either so it’s really hard to say either way.

In short, ammonites are an amazing group of extinct invertebrates, but they are also a total mess when it comes to soft-tissue reconstruction.

Scene 6: “Frozen sea” off Antarctica

Baseless speculation

The “frozen” sea

We are once more treated to a fictionalized “ice house” version of the Mesozoic. This time in Antarctica where we are shown sea ice that, according to the Megathread, is several centimeters thick. As with Ice Worlds and Scene 4 from Islands, this is an interpretation that relies heavily on the PP-commissioned climate models that I discussed about there. Also, just like those episodes, the same problems persist. However, now we have the added elasmosaurid problem.The build of elasmosaurids involves a stocky body that extends onto a extremely long neck, with some species having the longest neck to body ratios of any animal ever. These long necks end at small heads, similar to sauropods. That makes the head and neck an area of high heat transfer, which is a terrible shape to have if one is frequenting waters that are allegedly hovering around 0°C.

A recent computational fluid dynamic study by Marx et al. (2025) showcased just how difficult this bodyplan would be to maintain a stable head temperature regardless of thermophysiology and fat (blubber) content when the associated environment is this cold. The star elasmosaurid in this scene is Morturneria seymourensis, an animal known mostly from a skull and some cervical vertebrae (Chatterjee and Small 1989), so there’s a chance that the full body of this species is much stockier and pliosaur-like than envisioned in Prehistoric Planet. However, the discovery of the much more complete Vegasaurus molyi, and Aristonectes sp. in Antarctica does indicate that “normal-looking” elasmosaurids were found in this region (Okuyama et al. 2012; O’Gorman et al. 2013, 2015), including juvenile animals that would have an even harder time maintaining a high body temperature if these Antarctic waters were actually that freezing.

Double sins for this one.

Sociality, elusiveness, and the pod life of Morturneria

The first animal introduced in this scene is the elasmosaurid, Morturneria seymourensis. We are shown a couple nuzzling up to one another in a crack between the sea ice. Attenborough further informs the audience that these plesiosaurs are one of the world’s most secretive and elusive animals.

As is typical for the taxa featured in Prehistoric Planet, M. seymourensis is not known from much of anything (Chatterjee and Small 1989). It’s just a (good) skull with a few cervicals. No evidence for any type of social interaction is known for this species. The original publication does mention several other plesiosaur specimens from that region that were partially associated, but none of them align with M. seymourensis.This area appeared to be a popular spot for plesiosaurs, regardless of how much social interaction was going on. Similarly, the statement about their elusiveness is completely made up. We have no good idea on how popular or rare these species were at the time. Antarctic fossil hunting is still pretty new. There’s lots more to find out there.

As for all the pod-life scenes, yeah. No evidence for any of this either.

Warm-blooded plesiosaurs

As I mentioned in the Islands installment, Prehistoric Planet does away with any semblance of caution in “season 2” and once more Attenborough tells the audience that an extinct animal is warm-blooded, despite the lack of evidence. In this case, it is M. seymourensis. Attenborough then goes a step further and mentions that a layer of blubber in these reptiles helps maintains their body temperature in these waters. Naish expands a bit more on this in the Megathread, discussing previous research that has suggested that sauropterygians as a whole were warm-blooded (e.g., Motani 2002; Bernard et al. 2010; Fleischle et al. 2018). Some models rely on the outdated aerobic capacity model for support. Others lean too much on isotopic data to infer high body temp = high metabolic rate, which has been shown to be a rather weak correlation (see Baumgart et al. 2025 for a review), and still other models rely on estimated growth rate to insert an (arbitrary) line for when obligate endothermy starts. This last approach has been cautioned against for decades (e.g., Chinsamy 1994; Stein and Prondvai 2014) and even now as I’m writing this installment a new paper has come out from Chinsamy and Pereyra (2025) showing once more that the approach vertebrate paleontology has been using to determine growth rate has been very misleading and most likely wrong. The Prehistoric Planet approach seems to rely heavily on Antarctica being “too cold” for a bradymetabolic animal.

I’ll also note that part of the B-Roll for this scene shows young, extant notothenioids swimming around brinicles. I guess they must be warm-blooded too. 🙂

Mostly speculation

Unique feeding method of Morturneria

A large part of this scene involves the pod of M. seymourensis diving down to the bottom of the Antarctic ocean to sieve feed by scooping mouthfuls of sediment in their mouths and using their teeth to capture prey as they push the rest of the sediment out. It’s an interesting idea that has some basis in the literature (O’Keefe et al. 2017). It’s based largely on the wide mouth of this species coupled with the interlocking, splayed teeth. O’Keefe and colleagues suggested that M. seymourensis may have sieved food from mouthfulls of sediment pushed out by its tongue. The concept of a trench or “gutters’ formed by these feeding traces was addressed in the Megathread and an old post on Tetrapod Zoology.

It’s certainly an interesting hypothesis, but one in need of far more data to support it. I think some form of filter feeding seems likely (assuming the skull of M. seymourensis doesn’t have its jaw diagenetically deformed). I’m less certain (but amenable) of the soil eating. Also, it is nice to see a different example of plesiosaur hunting styles, even if this one doesn’t have anything to do with the long necks.

Final sin count: 29

References

Street, H.P. and Caldwell, M.W., 2017. Rediagnosis and redescription of Mosasaurus hoffmannii (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and an assessment of species assigned to the genus Mosasaurus. Geological Magazine. 154(3):521-557.