For a primer on this blog series and an FAQ see here.

| Other Episodes |

||||

| Coasts | Deserts | Freshwater | Ice Worlds | Forests |

| Islands | Badlands | Swamps | Oceans | North America |

This episode features contributions from the following paleontology consultants:

- Victoria Arbour

- Steve Brusatte

- John Conway

- Alexander Farsnworth

- Scott Hartman

- Robert Spicer

- Paul Valdes

- Mike Widdowson

- Darren Naish

Scene 1: Deccan Traps, Central India

Baseless speculation

Dangerous migration

The scene starts off with a herd of Isisaurus colberti traveling across a volcanic hellscape. Attenborough informs the audience that this herd is in search of their ancestral, colonial breeding ground. Attenborough tells the audience that the females make this perilous journey every spring.

For starters, all we know of I. colberti comes from a single specimen (see Wilson and Upchurch 2003 for the full rundown). Though well preserved, it was not associated with any eggs, so we have nothing to go on for reproduction. I. colberti was found in the Lameta Formation of Central India. The sedimentology of this formation indicates a much lower-energy environment (slow rivers and lakes). More importantly, the Lameta Formation is older than the Deccan Traps (e.g., Srivastava et al. 2015). Exactly how much time between the older Lameta Formation and the younger Deccan Traps is hard to say, but the time span is long enough that I. colberti may have already gone extinct by the time the eruptions first started. Not that it matters because it’s unlikely that any dinosaur was living around the hyperactive Deccan Traps area (fossils are not found in the basalt of the Deccan Traps but rather the intertrappean beds that formed during less volcanically active times). Naish notes as much in the Twitter Megathread for this episode. Unfortunately, it’s this volcanically active time that is being shown in the series. I will note that the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment for this episode has Naish stating that we do have data for nesting in these intertrappean beds. From what I’ve been able to gather, there are some data to show that some species (including unnamed sauropods) were laying eggs during these volcanically stable times too, but the vast majority of egg fossils in this region come from the older Lameta Formation (Khosla and Lucas 2020).

More speedy incubation times

Attenborough informs the audience that the volcanic landscape in which the I. colberti females are laying their eggs results in incubation times of only a few months. The problem here is that we have no idea of how long sauropod incubation times are, so we don’t have a baseline to compare to. Volcanic soil may influence the incubation times by maintaining a high temperature for the developing hatchlings. Naish points out in the Megathread that some megapodes use this method today (e.g., Bashari et al. 2021). I would add that this has also been hypothesized for Galapagos land iguanas (Conolophus cristatus; Werner et al. 1982). As discussed in the Ice Worlds installment, we do have evidence for at least one sauropod species doing this (Fiorelli et al. 2012), though via hydrothermal soil heating rather than direct volcanic heating. This is also brought up in the Prehistoric Planet Uncovered segment for this episode. That said, the absolute statement about incubation time is ultimately what is keeping this section in the baseless speculation category.

Mostly speculation

Nest site fidelity and colonial nesting sauropods

Isisaurus colberti are shown making a routine trek across this volcanic helllscape to arrive at their ancestral nesting grounds. As discussed above, we have no evidence for this in I. colberti but we do have some evidence of colonial and continual nesting in other titanosaurs. Namely, the Auca Mahuevo titanosaur nesting site (Chiappe et al. 1998) provides the strongest evidence for colonial nesting, whereas support for nest site fidelity can be found in several fossils from the underlying Lameta Formation (though, crucially, not for colonial nesting; Sanders et al. 2008). So, a bit of a mixed bag here.

Epidermal spines on the neck

The extensive dorsal spines seen on I. colberti were inspired by the dorsal “combs” on various iguanids. This inspiration garners some support from a diplodocid soft-tissue impression showing dorsal spines in at least one species (Czerkas 1992). This trait may have continued into the much more derived titanosaurs, or it may have been limited to only diplodocids, or even that singular species. It’s always hard to tell here. In short, we have no evidence for this in I. colberti,but we have some fossil support for this in other sauropod relatives.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Nest shape and size for Isisaurus

Attenborough describes the shape and size of the nest that each I. colberti female makes. As before, we have only a single specimen to go on and no eggs or nests to compare, but inferring nest shape based on other, related sauropods (including titanosaurs) is possible. I will add that Naish does a great job in the Twitter Megathread of highlighting just some of the detailed homework that was done to ensure nest shapes that were as accurate as can be. I wish the series had any of this and that these external behind the scenes bits had more of it.

Scene 2: Gobi Desert

Continued anachronism

Velociraptor…again!

We are once more “treated” to the out of time return of Velociraptor mongoliensis. Naish mentions throughout the Twitter Megathread that he knows the animal shouldn’t have been there but the show couldn’t simply say Velociraptor-like velocraptorine…except that is exactly what occurs later in the series. It’s clear at this point that V. mongoliensis was used in this series strictly for “brand appeal”. The general public knows (sort of) what Velociraptor looked like, so it’s good marketing.

Double sins for this one.

Baseless speculation

Young Velociraptor huddle together

The scene shows a group of hatchling V. mongoliensis huddling together in a side canyon. I would normally ignore this piece here, but in the Megathread Naish does discuss the “cuteness” of the babies in detail. Reminder here: we have no V. mongoliensis eggs, hatchlings, nor juvenile material. Comparisons to the behaviour of huddling babies require pulling from an oviraptorosaur fossil of three (possibly four) juvenile Oksoko avarsan (Funston et al. 2020), along with comparison to some birds. Such a broad brush distribution of a behaviour is questionable.

Return of the pack

As before, these V. mongoliensis are pack hunters, and as before, we continue to have no evidence supporting this proposal.

Mixed herd at an oasis

The other animals in this scene include Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis, “The Mongolian titan”, and Prenocephale prenes. All of these animals are making their way through the desert to reach an annual oasis. Though ephemeral oases were likely present in the Mesozoic, we don’t have any direct evidence for this in the Gobi. Similarly, we have no evidence for this mixed herding of sauropods and pachycephalosaurs. Also, the “Mongolian titan” is only known from a foot impression, so any reconstructions of it should be viewed with a grain of salt.

Tarbosaurus and the feathered mohawk

This scene sees the return of Tarbosaurus bataar. As before, the animal is portrayed with the feathered mowhawk that’s become all the rage since Bell et al. 2017 plucked most feathers off tyrannosaurs. So, it’s the same sin as before…and before…and before.

Pack hunting Tarbosaurus

T. bataar become the real threat in this scene as a trio of these theropods descend on the titanosaur herd. The animals are described as hunting as a pack, though we see very little of this. We currently have no evidence for any tyrannosaurid hunting together. Phil Currie produced the most detailed arguments for gregariousness in tyrannosaurids, describing bonebeds for Albertosaurus sarcophagus, Daspletosaurus torosus, and Tarbosaurus bataar (Currie 1998; Currie et al. 2005). However, these interpretations were not without controversy (e.g., Roach and Brinkman 2007) and Currie later walked back the push for cooperative hunting and focused more on evidence for gregariousness (Currie and Eberth 2010). So, we have some evidence to support tyrannosaurids gathering for something, but no real support for pack hunting as shown in the show.

Velociraptor traps Prenocephale

Although we have a two titanic animals in this scene, it’s really the smaller dinosaurs that end up taking the spotlight. The V. mongoliensis pack chase after the spooked P. prenes as they rush to get away from the spooked titanosaurs. One V. mongoliensis chases a target P. prenes up the cliff towards another V. mongoliensis in waiting. When the scared P. prenes runs by, the ambush-ready V. mongoliensis dropkicks it down the cliff. Attenborough informs us that by working together, the pair have secured a meal for the whole family.

So, to summarize:

- Pack hunting

- Skilled trap setting on par with lions

- Dropkicking the prey down the mountain

- Doing this to feed the family

I should give this whole scene five sins for just how much speculation is present, but I’ll leave it at two. Naish argues in the Megathread that a version of this type of ambush behaviour is widespread among birds, but we only really see it in a single species (Harris hawks) with the rest consisting of examples of seemingly rare behaviours in other raptors (Ellis et al. 1993).

Missed opportunity…again

Waste of a claw

We are once more treated to a hunting dromaeosaur that doesn’t use its sickle claw for anything. They didn’t even use the claw to help open up the carcass.

Scene 3: More Gobi desert

Baseless speculation

Corythoraptor out of place

We are reintroduced to Corythoraptor jacobsi. However, as Naish points out in the Twitter Megathread, C. jacobsi is not actually known from the Gobi desert (it’s from Guandong, China). So, the animal is out of place…again.

Dedicated parents

We are shown a group of C. jacobsi nesting colonially and Attenborough informs the audience that they are some of the most doting parents in the dinosaur world. That’s a bold statement to make for an animal known only from a single skeleton. Even other oviraptorids only show evidence for potential egg brooding, not colonial nesting or any other potential behaviours to indicate deeply dedicated parenting.

The broken arms of Corthoraptor and nest arrangement

Various shots in this scene show C. jacobsi parents moving their eggs into position with their mouths. This, despite completely functional forelimbs. Just use the damned forelimbs! There is nothing in the range of motion that would have prevented the forelimbs from being used here. As with Ornithomimus edmontonicus in Ice Worlds, forelimbs are reduced to vestigial, partial display organs.

There is also the issue of C. jacobsi moving the eggs into position at all. It’s more likely that the eggs were arranged that way when they were originally laid. Naish brings this up in the Megathread and indicates that this was a production mistake. So, I’ll let that sin slide.

Brooding males hunt at night and take turns guarding the colonial nests

We are shown the C. jacobsi males go out to hunt for food at night and guarding the nests during the day. It’s a possibility, but it’s one that lacks any data to support it one way or the other. It’s just as likely that the brooding parent sat on or by the eggs for months on end. Maybe leaving once a week to search for food. Similarly, there are no data to support any oviraptorosaur doing colonial nest guarding.

The broken arms of Kuru

The next dinosaur to appear in this scene is the velociraptorine, Kuru kulla. The theropod is shown as an egg thief, sneaking in to steal eggs from the wary C. jacobsi and eating as much as possible before getting caught. The concept isn’t far fetched, as Naish discusses on the Twitter Megathread, there would have been an abundance of eggs during he Mesozoic as practically every large amniote was an egg layer at the time. So, it’s likely that several predators would take advantage of egg eating. That’s said, using a “documentary” as a vehicle for one’s pet hypothesis is a bit poor form. Regardless, the concept of a velociraptorine eating eggs is fine. Even stealing eggs is within bounds.

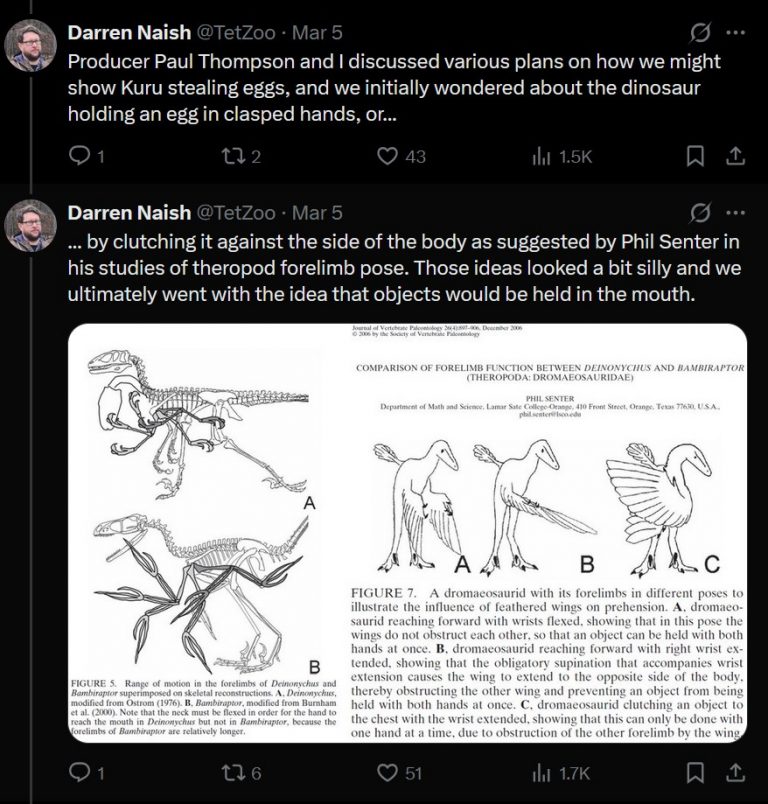

However, why do we once more see a theropod with completely functional arms acting like the arms are a useless appendage? Dromaeosaurs had arms that had the required range of motion to hold onto objects like eggs (Senter 2006). Even with the limitations of osteology-only based ROM studies, dromaeosaurs had what it took to hold things. So, why oh why was this not done here?

Apparently, because it looked silly.

That this choice to drop something biomechanically plausible and potentially even likely, because it looked silly seems to fly in the face of a show that alleges to show animals doing things that may seem strange and out of the ordinary. The 1985 documentary, Dinosaur!, was able to show that just fine. It’s hard to imagine why a show over thirty years later couldn’t do the same.

Double sins for this one.

Parental feeding in Kuru

The female K. kulla that successfully stole an egg from the colonial nesting C. jacobsi returns back to her brood (of course) and offers her spoils to her hatchlings. We are once again treated to a version of dinosaur parenting that may never have existed. Parental feeding is rare in extant reptiles and is hardly found in basally branching birds (e.g., no parental feeding is seen in paleognaths). This seems to be a feature that evolved later in Aves as opposed to being inherited from dinosaurs. That doesn’t mean that some dinosaur species couldn’t have had parental feeding, but PP makes it seem like all dinosaurs were parental feeders.

Kuru calls her young with a purring sound

K. kulla brings a stolen egg back to her nest and to get the attention of her young she emits a “purring” like sound. I wouldn’t normally bring up this bit as it’s standard speculation except that Attenborough explicitly mentions that K. kulla uses this purring sound to call her young. We have no evidence for this. Studies into reconstructing dinosaur acoustic abilities are still in their infancy. We are not sure what (if any) sound an animal like K. kulla would make, much less the behavioural implications of said sounds.

So it can be done

Kuru the Velociraptor replacement

The velociraptorine, Kuru kulla is the other star dinosaur in this scene, It’s worth noting that K. kulla is introduced by Attenborough, who gives the animal’s full taxonomic name rather than just the genus. This may have been done to avoid confusion with the human prion virus, kuru (see also the original description for K. kulla by Napoli et al. 2021). Attenborough tells us that K. kulla is a relative of Velociraptor mongoliensis. In the Megathread, Naish mentions that “they” wanted to go with a different theropod from V. mongoliensis again and so opted to go with the (at the time) recently described K. kulla (Napoli et al. 2021). The taxon is known from a single, partial skeleton. It’s not a particularly informative skeleton but it is enough material to determine that K. kulla was a velociraptorine.

So, that effectively means that our Velociraptor replacement is just a “reskin” of the V. mongoliensis model from prior episodes. However, it now has a period-correct animal in its place. Thus leaving us with a question of why V. mongoliensis was used at all if K. kulla was already available? I think that for “season 1′” it may have been too early to stop the naming scheme, but by the time “season 2” rolled around they could have easily fixed this.

Mostly speculation

Dudes only…again

As discussed previously in the Ice Worlds episode, the idea of paternal-only nest guarding for theropods has some support in the literature (Varricchio et al. 2008), but remains controversial in part due to the heavy bias towards birds in that study. So, some scientific backing but certainly not enough to distribute this so broadly across Theropoda.

Wings for shade (not a sin, just production weirdness)

In this scene we see the male C. jacobsi using their wings as makeshift shade for the eggs during the heat of the day. This is largely based on a specimen of Oviraptor philoceratops found on top of its nest in a position that could have covered its eggs with its potential wing feathers (Norell et al. 1995). We have no direct data for plumage in O. philoceratops but can infer from related specimens like Caudipteryx zoui. The only real complaint I have here is more of a production complaint in that the wing feathers for C. jacobsi are too short to effectively cover the eggs.

Kuru with the better night vision

In the scene with K. kulla sneaking around the nesting site, Attenborough informs the audience that K. kulla has better night vision than the oviraptorosaurs. There are no primary data to back up this claim as K. kulla lacks almost all its orbital anatomy (Napoli et al. 2021). One could infer that this velociraptorine was more crepuscular or nocturnal than the oviraptorosaurs based on scleral ring data from V. mongoliensis and Citipati osmolskae(e.g, using equations from Schmitz and Motani 2011), but that requires stretching the data a fair bit.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Gular flutter (a sin for not being explicit)

During the heat of the day we see the male C. jacobsi rapidly moving the floor of their mouths in a cooling behaviour referred to as gular flutter. As a behaviour we lack the means of saying for certain that these theropods would use this technique to cool their brains down, but they would have the necessary hyoid anatomy needed to move the floor of the mouth like this, and anatomical reconstructions have shown that the needed vascular supply would have been present in the roof of the mouth (Porter and Witmer 2020). Plus, gular flutter is widely distributed across Sauropsida. So, it has a good chance that these dinosaurs could use this behaviour.

Sadly, the show never mentions this interesting behaviour.

Annoying trend in the series

Slow moving nictitating membranes

Seeing CG dinosaurs using their nictitating membranes is neat and all, but the dinosaurs in this series blink very slowly. They also blink way too often. Extant sauropsids with nictitating membranes (all of them, I think) blink much faster than this. The point of the membrane is to rehydrate the eye. Most nictitating membranes are also clear, so the movement hardly obstructs vision. I wish the show runners were less enamoured by the appeal of a “third” eyelid and focused more on how real animals use it.

Scene 4: Even more Gobi Desert

Baseless speculation

Tarchia the desert specialist

This scene opens on the ankylosaurid, Tarchia kielanae. Attenborough introduces the species by mispronouncing the name as Tar-chee-ah instead of a guttural Tar-hee(guttural)-ah. I’m not going to ding the show for that since most people mispronounce the name (one of the myriad downsides of not using Latin and Greek as a base for taxonomic names). It doesn’t help that Maryanska didn’t provide a pronunciation guide when she originally named the taxon (Maryanska 1977).

I will ding the show for saying that T. kielanae was a desert specialist. As Naish points out in the Megathread, we don’t really have any evidence for this animal being a specialist as opposed to a seasonal visitor. This leads to speculation on colouration in relation to UV exposure too, such as the “eyeliner” for UV protection. We have no evidence for that, despite the potential use here.

There are also some uncertainties surrounding the overall armour placement, but this was all covered well in the Megathread, so no real fault there.

Flaring nostrils

T. kielanae was given flaring nostrils that were loosely based on the smooth-muscle controlled narial muscles of crocodylians. The latter’s muscles are apomorphies of croocdylians (somewhere down the tree of Crocodylomorpha) and are related to keeping water out of the nasal passages. There is no reason to assume that a terrestrial ankylosaur would evolve this structure. The concept was that it would help keep sand out of the nose during sand storms, but it’s doubtful said sandstorms were that frequent. We do have some desert-living lizards that have the ability to close of their nostrils to keep sand out, but that ability involves “inflating the nasal epithelium and closing off the nose that way (Stebbins 1943). It’s also limited to lizards that bury themselves in the sand. I doubt T. kielanae did any of that.

To his credit, Naish admits that the flaring nostril bit went too far and was overused for the dinosaur models.

The mental map of the desert

The T. kielanae in this scene are said to have developed a mental map of the desert that keeps them from getting lost. This is similar to the statement made in the Deserts episode and has an equal lack of supporting data for it.

Mostly speculation

Waddling Tarchia

This is a difficult movement to nail down and there has not been a lot of work on ankylosaur gait. The Megathread goes into a bit of detail on the difficulties that he and the production team had in figuring out a gait that worked. I would have been happier with a wider waddle and more of a forearm swing, but it’s all equally speculative at this stage. Biomechanically, it’s within the realm of plausibility.

Drinking Prenocephale (not a sin but a note)

Another taxon in this scene is the small pachycephalosaur, Prenocephale prenes. We are shown the animal dipping its mouth into the water and then flipping it back to drink similar to birds. We have no biomechanical data for how these dinosaurs would drink, but we do know that drinking behaviours have evolved several different times. Cats drink different from dogs, which drink different from snakes, which drink different from lizards, which drink different from humans. So, it’s all in the realm of plausibility here. Not a sin (aside from not mentioning this), just an observation.

Battling Tarchia

Towards the end of this scene, the young T. kielanae find themselves battling for oasis territory with an older adult. The defensive interactions and behaviours are all made up here. Though, I will say that we do have some evidence to support ankylosaurids using their tails on one another (Arbour et al. 2022). This paper would have likely come out after this episode had finished but the idea of intraspecific combat has been around at SVP talks for years prior. Still, the details of these interactions (which were all bluffs in this case) are unknown.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Mighty hot desert

Attenborough informs the audience that the sand temperature in the day could get as hot as 71°C (~160°F). That’s phenomenally hot. About as hot as the hottest recorded temperature for the Lut desert in Iran. That is very hot. I’m not sure where that paleoclimatological data for that is coming from. The Mesozoic was a very hot time, so the idea that a desert area would get this hot is not out of the realm of possibility. I would have shied about from a concrete number, though.

The nasal air conditioner

At one point we get a closer view of the nose in T. kielanae and Attenborough informs the audience that T. kielanae uses its nose as an air conditioner, allowing it to conserve water with every breath. This is based on both anatomical inference for the nasal passages of related ankylosaurs (Euoplocephalus tutus) and modeling simulations testing the efficacy of this anatomy (Witmer and Ridgely 2008; Bourke et al. 2018). So, no real complaints with this interpretation here. The reason for the ding is due to the need to clarify that the findings from the modeling study showed that this effective air conditioner was something found in most (possibly all) large dinosaurs. So, it’s not an adaptation for desert life so much as an adaptation for being very big.

Social ankylosaurs

T. kielanae is shown as a group of young animals living together and then later interacting with another, larger adult. We don’t have any direct evidence for social living in T. kielanae but we do have support for this in the relatively closely related Pinacosaurus grangeri (Currie et al. 2011). I’m always leery about attributed behaviours across phylogeny like this, but at least this time the taxa are pretty closely related to one another.

Scene 5: Return to the Deccan Traps

Baseless speculation

Hatching at just the right time

We return to the first scene in the episode, but several months later. The baby Isisaurus colberti have hatched. Attenborough informs the audience that the young hatch during the time of the season when the winds have blown the low-level CO2 fog away. This requires either a phenomenal amount of stability in this region (known for its instability) or eggs that are capable of suspending development (diapause) until proper conditions arrive, such as in Snake-Necked turtles (Chelodina, Fordham et al. 2006). We have evidence for neither, though the latter has likely never been investigated).

Puny lunch boxes

After the young hatch they begin their trek down the caldera to greener pastures. Attenborough informs the audience that the young I. colberti have only a few days worth of yolk to keep them going. There is no evidence for this one way or the other. That said, a larger yolk supply would be more realistic for animals that don’t have post-hatching parental care. The young I. colberti could have had a month’s supply of energy from their yolk reserves. This part felt too endothermocentric.

Mostly speculation

Coprophagy

The hatchling I. colberti are shown eating “fresh” dung that their mothers left behind during the egg laying process. We don’t know if any dinosaur hatchling did this. However, as Naish points out in the Megathread, we do know that other hatchling reptiles have been observed doing this (e.g., Troyer 1984) and for the reasons mentioned in the episode (getting the adult gut flora). Also, as mentioned in the Megathread, these hatchling may learn the pheromones of their mothers this way (e.g., Moreira et al. 2008). Whether these hatchlings ever rejoined the herd or just start a herd of their own is completely up in the air. They could also have been solitary. We just don’t know that part.

The only real ding that I would give here is the idea that the several month old poop would be of any real use to the hatchlings. Extant hatchling iguanas eat fresh (or fresher) feces from adults (Troyer 1982). There is a better chance of ingesting living bacteria this way.

The long trek home

The creche of hatchlings continue on a long journey to their forest home. Attenborough informs the audience that this is the forest that their parents came from, thus indicating a degree of generational migration taking place here. Though we have no evidence that this species or any other dinosaur species did long treks such as this, we do have multiple observational studies showing that this type of generational movement is widespread among reptiles (e.g., Southwood and Avens 2010). So, it’s at least plausible.

Reasonable inference…but still speculation

Synchronized hatching and vocalization

We are shown the I. colberti hatchlings synchronize their hatching via vocalizations to one another from in their eggs. This has some solid basis in extant reptiles such as crocodylians and turtles (e.g., Vergne and Mathevon 2008; Ferrara et al. 2012), as well as in some birds (e.g., Rumpf and Tzschentke 2010). So, it may have been present in some dinosaurs too. We have no way of knowing which ones at this stage, but it is a reasonable inference.

Mass of hatchlings successfully survive (not a sin, just a wish for more hunters)

As the young I. colberti continue towards the forest they encounter some hungry Rajasaurus narmadensis, which go to town on the mass of hatchlings. We are only shown two R. narmadensis and it would have been nice to see some pterosaurs and maybe a predatory lizard, crocodyliform, or mammal joining in as well, but the idea was to make it clear that of the hundreds of hatchlings that were born, only a small fraction survive. In the Megathread, Naish discusses this as a predator swamping strategy (think of hatchling sea turtles). Though we can’t be sure that I. colberti did this, the known nest size of sauropods and other dinosaurs, coupled with our current understanding of post-hachling care in sauropods, would argue in favour of this inference. That said, the point of predator swamping is to overwhelm the mass of predators that come to town. Having only two hungry theropods is a bit disappointing here, if understandable from a production point of view. All that said, we can’t really quantify how many would have survived such an encounter (100? 1? 1000?).

Annoying trend

Chatterboxes

All of the hatchling I. colberti cannot shutup for the duration of the scene. They make sounds coming out of their eggs. They make sounds as they get their bearings and start walking to the forest. They make sounds when one of them falls to their death near a mud pot. I know it’s antithetical to mass media culture, but hatchling animals are usually very quiet. Especially when those hatchlings are precocial and need to avoid attracting the attention of predators. These little chatterboxes were giving away their positions every few seconds.